I don’t like PEE. I have never really liked it. Firstly, because it restricts and secondly because a lot of the time, the very students it is designed to support, just don’t understand what on earth it means. Before I worked in education, I had never heard of a PEE paragraph, I wasn’t taught them at school, didn’t use them at university and yet I am a fairly competent essay writer. I recently read a year 7 essay that my uncle had written in 1960s, not a PEE in sight and would have easily been top marks at GCSE.

Before I trained as a teacher, I was a TA and lost count of the amount of times students would stare at me blankly saying, ‘I don’t get it’ when asked to write a PEE paragraph. And then I taught it, and they still didn’t get it. The amount of times I have read posts on Twitter from teachers pulling their hair out because ‘they can’t write points’. Then ‘they’ probably don’t know what a point is and instead of flogging something to death that isn’t working, then why not actually change the way it is taught?

In 2015 I was intending to go to Researched in Swindon, but at the last minute wasn’t able to. At this time I was teaching PEE, but like many people was just frustrated that they weren’t getting it, some just weren’t going into enough detail and others just wrote hardly anything, saying it was too hard. Luckily ResearchEd was recorded and I got to see what I actually wanted to see – the brilliant Louisa Enstone talking about her research into stopping using PEE. You can watch the video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2KVt1RzWbuY

and read about it here:

https://www.nate.org.uk/file/2017/03/NATE_TE_Issue-13_33-36-ENSTONE-FINAL.pdf

So, bolstered by these ideas, I went back into my classroom determined to try something new and a few years later, I am completely convinced. PEE is an acronym wholly made up in a desperate attempt to get students to pass, and yet what has happened is that students have become completely dependent on it. I have picked up classes in later years and moved them away from PEE, but they keep slipping back because, along the line, they have somehow come to believe it is the ‘right’ way to write, it is the magic formula – except it’s not. It isn’t their fault, and I’ve taught students who get very nervous and antsy when I try and break the PEE addiction, whilst others suddenly flourish, because they can actually write what they are thinking, and not have to follow a formula.

So the basis is this – there are 3 basic things that we need to consider when we are analysing a text.

- What is the writer telling us about the character/theme/setting?

- How do they use language/structure/form etc to do this?

- Why are they doing this?

These 3 questions get them thinking and allow them to explore ideas. Asking them to write a Point and find some evidence just doesn’t….and explain what exactly? Students can become stuck because they feel like it is a puzzle that has to be put together the ‘right’ way. But it really doesn’t. The 3 questions, for those who worry about exams, cover the basic AOs. If they are answering those questions, they are hitting the assessment objectives. I don’t refer ever to assessment objectives, which I know some won’t agree with, but when you are 15 years old and you have 9 different subjects with different assessment objectives, you can be forgiven for not remembering what each objective is. If I said to you, have you include AO2, you might just nod and smile, but if I ask you if you have thought about how the writer uses language you might be much more confident in your answer. I believe AOs do have their place, certainly at A level where there are less subjects and a more in-depth understanding of exam criteria, there most certainly would be a reference to AOs, but at GCSE it really isn’t essential to students passing; there is no AO test on the paper.

Once there is an understanding of the basic questions, they can then be layered up with more questions. I then add:

- What do they want us to feel as a reader?

- How does the writer use key words to show this?

- How does it tell us something about a time that a text was written in?

- Why have they chosen that language over other language?

- Why might they want us to interpret it in different ways?

Or anything else that might fit with whatever we are studying at the time – the questions can be fluid, but always be, what, how and why questions.

So what does it mean for their writing? Year 11 are currently reading The Sign of Four. We are reading chapter 4 where we are introduced to the character of Thaddeus Sholto. A basic question we might consider is ‘how does Conan Doyle present the character of Thaddeus Sholto?’

Using the ‘What, How, Why’ questions we first pool ideas and students are encouraged to make links to what they have already read.

Students have a list of the questions to consider, or I might add to them in discussion. Then comes the bit where it makes all the difference – they write up their ideas but have to follow no particular formula, just know that they thinking about What, How, Why in their answer.

Student 1 might be a little less confident and follow what might seem natural – What, followed by How and then Why:

Student 2 however, might think they might want to start with the Why ideas from the planning and lead into the What and How:

Whereas Student 3 has gone for the How followed by the What and Why

Obviously this example uses the same ideas to show that the order they are written doesn’t actually matter, in reality, you start to see much more of a variety in their writing. The point is simply that they don’t need to follow any particular formula, they just need to get their ideas down and write. Allowing students the freedom to express themselves in the way they feel most comfortable means that they do write and they don’t waste time worrying about whether it is ordered correctly. The exact same ideas can be expressed in a number of different ways and sometimes this then leads them down different pathways and ideas that they were too afraid to put in a PEE paragraph because they didn’t actually know where it should go, so didn’t bother.

Whenever I have discussed this on Twitter, there has always been those that suggest that there are those students that still need structure. Personally, I would argue that in many cases it is exactly those students that struggle the most with a PEE structure. The constant ‘fill in the grids’, or ‘match the quote with the point’ tasks, don’t get to the core issue – many just do not fundamentally understand what Point and Explain actually mean. They may understand that evidence is directly from the text, but in an exam situation, when they can’t think of a point they don’t even get as far as evidence, because the PEE structure tells them they have already failed, so they don’t bother.

So hopefully, here is an example that might change your mind. This is a target 1-4 class. The average target is 2/3. But because I’m mardy old rebel, they will all get 4s and above if it kills me…we may come back to this in 2 summer’s time. They have been studying Blood Brothers and we were preparing for our first go at an essay.

Firstly, in this case, we tackled the question itself using What, How, Why – I wrote down exactly what they said:

Then we came up with the first set of quotes together and analysed them using What, How, Why, being careful not to put them in any sort of hierarchy. The discussion about these ideas was much more than the bullet points might suggest, but too much in the way of notes might encourage them to simply copy. I have also been working on emotions and feelings with this group, for various reasons, so that was added.

Then they were asked to write it up as a paragraph, the only thing I asked them to do was think about the connectives they used to show similarity and difference. They were nervous at first and asked for a sentence starter, the sentence starter I gave them was….In Act One…They didn’t ask for anything else after that.

Student 1 went with a What, How, Why structure:

Student 2 started with the Why:

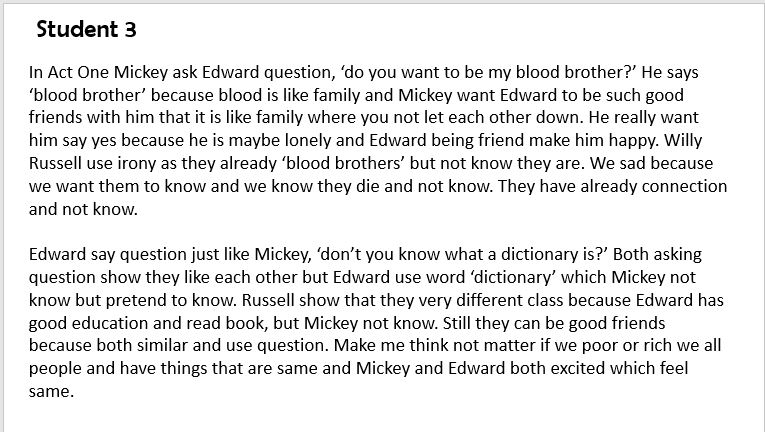

And Student 3 started with the How, leading into the What and Why. Student 3 is a New Arrival to the country

I truly believe that if I had asked them to follow a PEE structure they would have struggled because they would have worried that their ideas were not in the right order. Although we have a little way to go, I am personally very proud of them for showing their ideas and thinking – in an exam situation they would have covered all the AOs to an extent and they have all shown that they have read and understood that section of the play. Student 3, in particular would really have struggled without a bit of freedom to just tell me their ideas.

So this is why I no longer PEE (like many teachers quite literally during an average school day). I am completely convinced now that it is not the best way for students to write. I often wonder in fact where and when it was actually invented, when was it decided that student needed this strict acronym to follow? I can also categorically say that it makes marking 30 essays a much more pleasant experience and in higher ability students it has encouraged a greater free-flow of ideas and personal academic style. It hasn’t been without its issues; I have picked up students later in their school careers who really pushed against trying to think in any way but PEE. It also is not used across my department, so when we have swapped about for revision sessions and masterclasses, I have had to explain that they haven’t been taught to use PEE. Other subjects also still use PEE. But I am personally content, after sets of results, that What, How, Why allows a student to think, explore and most importantly, to write their ideas in a way that they are comfortable with.

I have sheets that I have laminated for students whenever they are writing, if they feel they need support. I think it needs adapting further to be even less formulaic, but if you would like a copy it is here

Update:

Since writing this blog I have been lucky enough to present and talk about this very topic to many teachers across the country at various events from PiXL meetings to conferences. It is the topic I get asked about the most, and both my DM and emails are often filled with people talking about how much of a difference it has made to their students’ writing. The absolute highlight of the last few years was seeing the strategy suggested by AQA in an examiner’s report as an ideal way to get suggests thinking about a text.

And it works. Of the students that you see above, 4 of the higher ability class scored full marks on at least 2 sections of the Literature Paper each and 9 of 25 scored 1-2 grades higher than target. Interestingly, it had a bigger impact on Language scores, where 12 of 25 scored 1-2 grades higher in their exams. This was all in the 2019 summer series, which was obviously the last set of exams where I could test data robustly.

The lower ability class were due to take their exams in 2020. They were a much smaller class of 12 but in teacher assessed grades (basically taken mostly for us from mocks) 6 of them achieved a grade over to grade at 4s and 5s. The majority of them achieved their target grade although 3 moved over to a foundation skills course. I personally believe that they would have done well in the actual exam, however obviously there is no actual data from the exam boards for that cohort.

As with most things in education, it is very difficult to say whether that one thing improved their writing. Unless you have control classes etc there are so many different variables in teaching that it is impossible to say that one thing improved their writing. But I believe that it did, just because it allowed a bit more freedom and pushed thinking by using 3 basic questions.

On a side note the first cohort I mentioned were also not taught the acronyms of SISTER of DAFOREST for persuasive/argumentative writing, instead being taught the fundamentals of rhetoric. Their Paper 2 Question 5 answers were significantly higher than in similar cohorts in previous years. Another win for not using acronyms.

I think what/how/why comes with a caveat though. It is not a replacement formula. Instead it is a way to encourage analytical thinking. The trick is to make sure that students have a toolbox of everything that makes good academic writing, and are asked the questions continuously that will push their thinking and will inevitably then trickle into their writing.

I will leave the last word to a student who came to see me after sitting their exam and said, ‘Miss, all I could hear was you saying, ‘but how do you know that’ and ‘but why?’ Everything is always, ‘but why?’ ‘

Thank you Becky. I am really keen on using this – I keep saying to my students that I don’t want PEE to be used in their writing.

This offers and excellent alternative and I will be using it actively with my Year 10s and 11s as well as my KS3 classes.

LikeLike

I’m so glad it helped. I’d love to hear how it all goes!

LikeLike

Thanks for such brilliant insight! I don’t remember ever being taught how to write essays at school. We just had to do it. It I think this would have been extremely useful and not only in analyses of texts. You can use those questions to help students write deeper, stronger and more meaningful fiction too. The simple question of “why?” is one of the main questions I ask as a writer when I’m working on a story. Why is my character reacting that way? Why do I want this scene to be like that? Etc. I had written a lot more to this comment before my phone deleted it all by mistake! But basically use the why/what/how questions to help students think more deeply about their own writing process – make them think like authors think. 😊.

LikeLike

I am studying to become a teacher of English in the Netherlands. For my studies I need to come up with assignments for my students to analyze books. I’m defenitly going to use this. By the way, they teach us PEE at University for answering questions on literature. Thank you.

LikeLike