This is a blog about ways to attempt to tackle the disadvantage gap. I’m not going to bang on about statistics and cite published research, I’m going to offer some practical ideas that I have used and borrowed from others, and have worked within a classroom setting in the hope that they might help others. So, if that’s not your thing, that’s ok.

When you look at media coverage of education during lockdown, two phrases pop up time and time again – ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘catch-up’. For those of us in education this is nothing new; we are constantly aware that there is a gap that needs to be filled, we spend hours considering what we, as educators, can do to try and close that gap. It sometimes seems like an impossible, un-ending task. And for those of us working in areas of high disadvantage lockdown has been particularly frustrating. There were nights at the start of lockdown I spent wondering how the hell I could reach out and actually teach anything valuable to students not accessing anything. But, like most of us this was replaced with a sense of resignation that I could only do as much as I could, and provide what I could. But we try, as we will try in September when we go back into the classroom, albeit in a new, stranger way.

A bit of personal background. I had a lovely middle-class upbringing. But my dad was a headteacher in one of the poorest areas of not only our city, but the country, who also worked with the Child Poverty Action Group. Mum was a SENCO also working with students facing disadvantage. After I finished my GCSEs I helped out at dad’s school and between that and the experiences I heard from my parents, my eyes were opened to the fact that things weren’t the same for everyone.

I spent a lot of my adult life as a single parent, and at times things were tough and I needed help, but I was still lucky that I had support to make sure that I never fell too far. But I was still aware that there was some stigma, and some assumptions placed on my children, as children of a single mother, that there were somehow at a disadvantage.

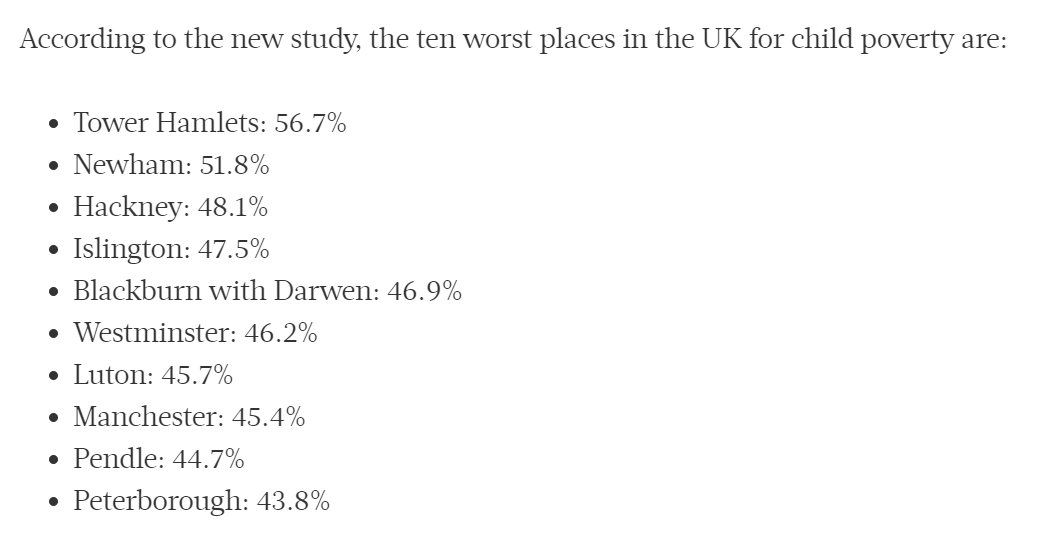

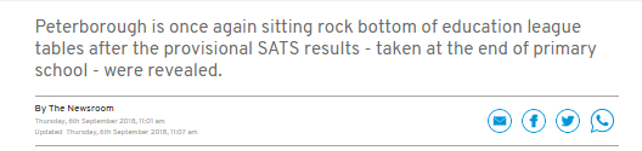

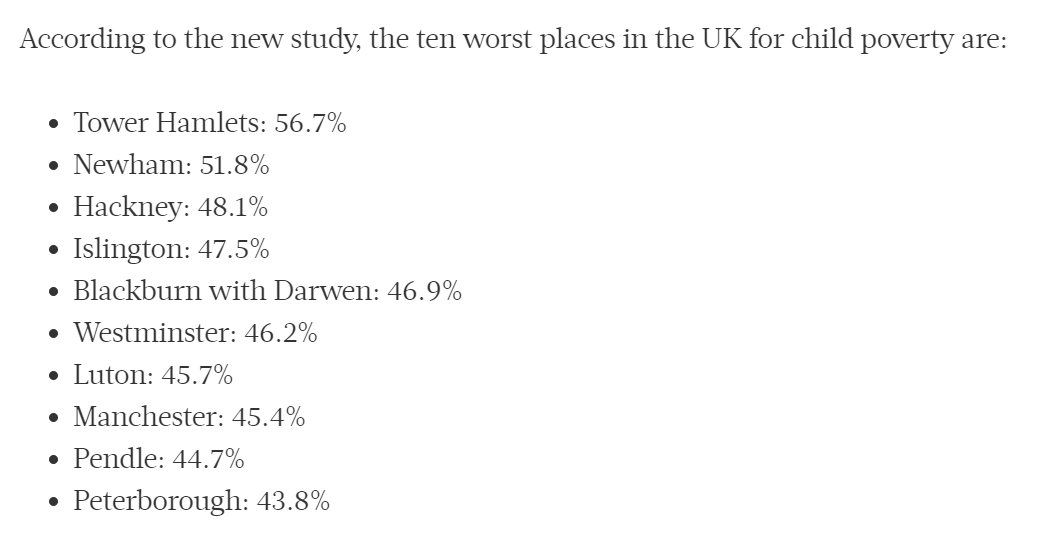

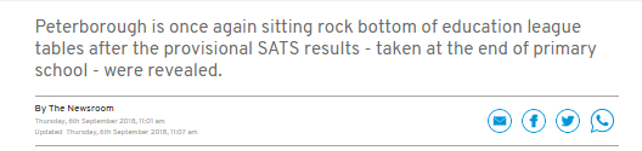

I have recently moved schools, and across the country, but at the beginning of lockdown, I was working in a school in Peterborough, and had done for nearly 17 years. Peterborough is one of those places that people don’t know (moving up North has made me realise just how many people have never heard of it) but it does have a couple of dubious honours, it is in the ‘top 10’ areas for child poverty in the country and in 2018 it was the very bottom LEA in the SATs table, in 2019 moving to second from the bottom.

The school I worked in had high levels of Pupil Premium students – in our last year 11 cohort, 50% of the 330 students were Pupil Premium. It also had high numbers (well over 50%) of students with English as an Additional Language and I remember being in a meeting where it was announced that there were over 80 languages spoken in the school. So, a school in a city facing significant difficulties, but with a wonderfully diverse cohort.

Year on year, like those working with similar cohorts, we did whatever we could to try and close that gap and to make sure that all our students had the same experience and opportunities. Earlier this year I presented to the local English department heads on some ideas and strategies that we had trialled and used within our department to try and close the gap – what follows are some of what was included. This is by no means a ‘must-do’ list; we all have different cohorts and different priorities. It is simply some of the strategies and ideas that we used, some of which definitely worked, others appeared to be making a difference and I think are worth sharing.

All students work included has been done so with permission from the students themselves.

Consistently High Expectations and Positive Relationships

How many of us have described a class as. ‘the bottom set’ and said, ‘they won’t be able to do that’? We have to be honest with ourselves and think about our own expectations – I’ve done it in the past, I hold my hands up. In fact, I don’t think I trust anyone who says that they have. Sometimes it is rooted in our experiences, and thus is hard to shake. So here’s my experience. I picked up a class in year 9. They were difficult, and when I say difficult I mean their behaviour was hard to manage, they had no interest in learning anything and every lesson felt like hell. I was an experienced and competent teacher but I would go home and cry and dread every lesson. But I would keep them until year 11, that was the way it went, and I, and them needed it to be the best experience it could be. As a class where there were nearly all PP students, I needed to do what I could to make it a positive experience.

These were students who believed they had been the bottom since way before they had met me, most since well into Primary. One of them actually used to mention their low SATs results continuously. There needed to be a mindset change and it needed to come from me. The first lesson of year 10 was me welcoming them and telling them that I didn’t care what had happened in the past, they were not leaving me without decent GCSE grades and that now on, we were in competition with top set and we were going to do better than them. I could lie and say they believed me straight away, but they didn’t. They pushed against me for weeks and months, but I stood my ground which was hard. Sometimes I wanted to just give in to their relentless telling me there was no point and they couldn’t do it, but I stayed firm with the help of some brilliant TAs, who went along with me. It was the little things I held onto. They were used to just arriving in their coats, sitting in their coats in a lesson and people letting it slip rather than causing confrontation. I just simply said, ‘top set aren’t sitting in their coats’ and would wait until all their coats were off until I started the lesson. It was constant praise, constant positivity and giving them really hard work. Really, really hard work, because in my head I wasn’t going to allow there to be a ceiling placed on these kids. I had consciously placed the fact that there were students with 1 and 2 targets to one side – and they never actually knew what their targets were.

And then some amazing things happened. I loved going to their lessons. Some of them would come and walk to the lesson with me after my PPA. They would actively seek out more work, they would have discussions about texts – one of the most interesting comments I have ever had about Paris and Capulet was from that class, and they wanted to do really well. In year 11 I sat and watched them proudly as they explained to year 7 what they had been learning. My heart swelled as they completed pages and pages of work in mocks, and I smiled as they insisted they needed to go and show the Head of Department what they had been learning (who brilliantly used to pop in and tell them how proud he was of them.) And then this happened, and I knew it had really all been worth it.

I have left the school at the end of their school career absolutely loving that class and being so very proud of them. I can’t tell you what results they have achieved, I know what I think they have and I will be travelling back for results day to see them get those results. But the point is this – we have to really honestly think about our own expectations, and that sometimes requires hard work, but it is ultimately rewarding.

The school I was at switched to mixed ability in an attempt to encourage changes to mindset. We also mixed GCSE classes so that they were a much wider banding of students, meaning there was no top or bottom set. Some schools use names or mix the numbers up, but ultimately, none of this matters unless we make sure that as educators we don’t allow either ourselves or others to place ceilings on a student’s learning. Interestingly, there will still be those that think they have a ‘weak’ class, even when classes are carefully mixed.

Students arrive with us already ingrained with assumptions about themselves, much of which may have come from a level of disadvantage. Talking to other teachers, this can perhaps be more pronounced for students in schools where there isn’t a high level of disadvantage. Students may ‘stand out’ more and really know they are at a disadvantage. In a school where at least 50% of your class are PP, you perhaps are less likely to treat a student differently, because you just can’t.

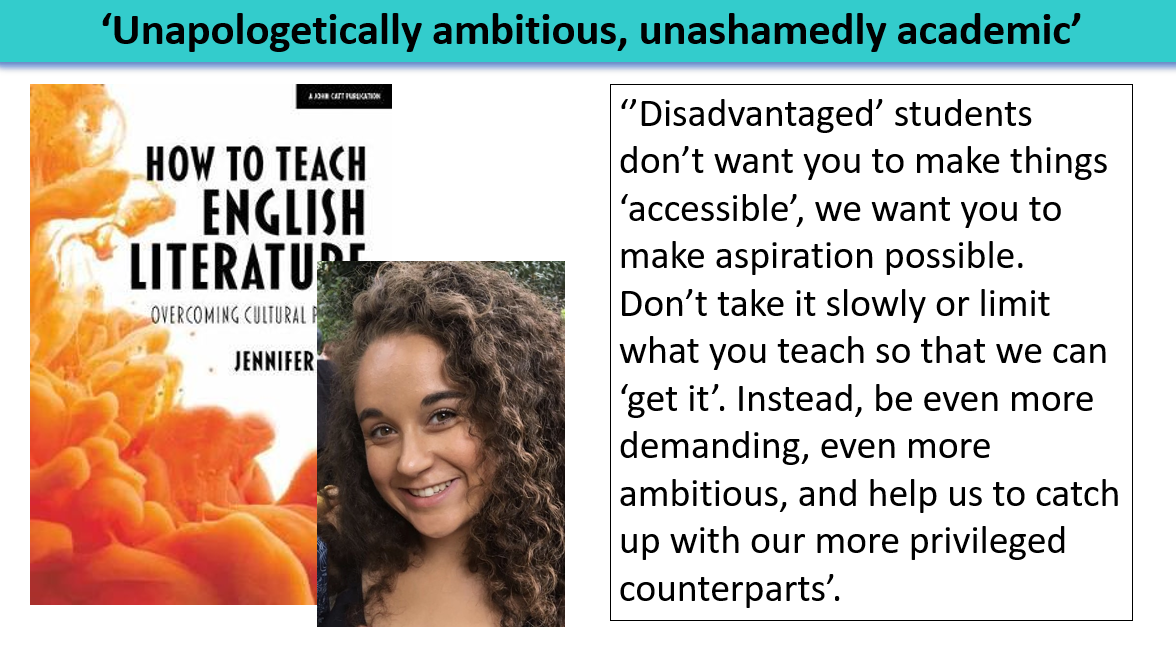

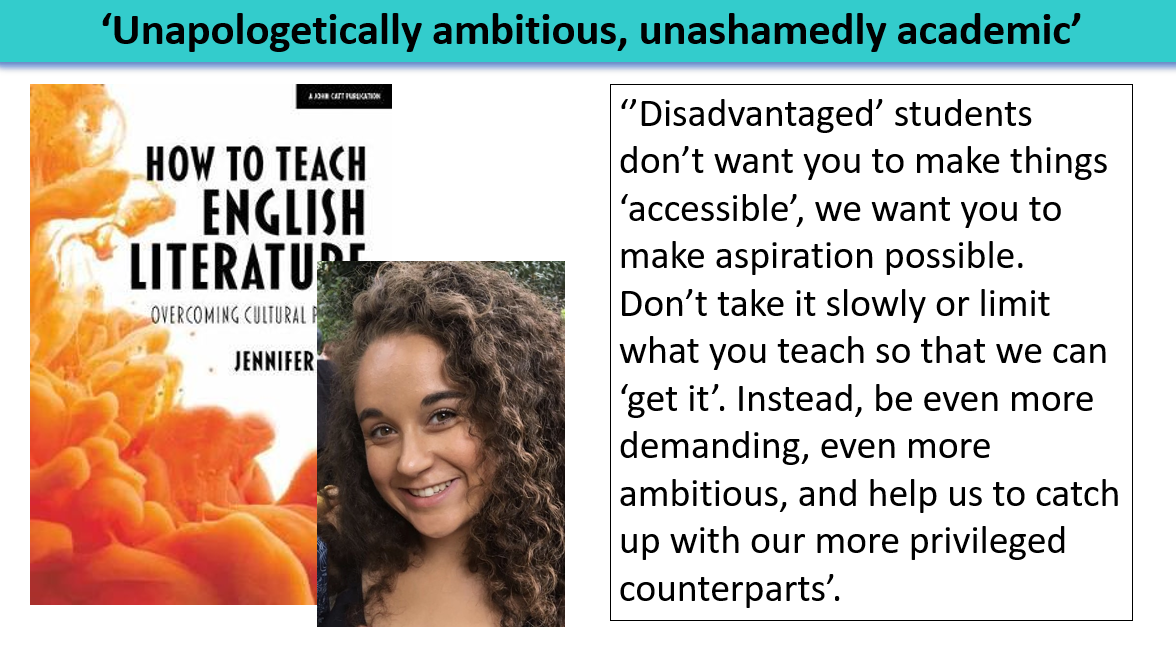

The wonderful Jennifer Webb, who I encourage you to listen to talk on the topic puts all this in a far more eloquent way than I.

Cultural poverty

Students from a disadvantaged background will be missing life experiences that their more privileged peers may have. We know this. Many children in Peterborough have never seen the sea, or much of the countryside, or hills. Every time I have taken students on a theatre trip, it is most of the students’ first experience of the theatre. When I went for my interview in Rochdale, the students who showed me round the school found the fact that I had stayed in Manchester (just up the road) the night before incredibly exciting, but proudly showed me the hills they could see from their windows. As schools we are very good at understanding what cultural capital our students have, we just need to unpick what they are missing and try and fill gaps where we can.

Jennifer Webb again:

It has never failed to amaze me what cultural information students might be missing. Google has been my friend many times when students suddenly admit they don’t know what something is. Below are a selection:

- Christmas – some students who don’t celebrate Christmas don’t have the knowledge about Christmas dinners, or Christmas morning needed to fully understand a Christmas Carol.

- Lighthouse – Again Christmas Carol – none of a year 11 class knew what a lighthouse was

- Swan – the poem Winter Swans. Some students had never seen one.

- Osprey – Some of you may remember the infamous Osprey IGCSE paper where students across the country had no idea what an Osprey was

- Straw – I spent half a lesson babbling on about Crook’s bed being made of straw in an Of Mice and Men lesson before realising none of them knew what straw was.

Some of this we can predict, knowing our cohorts and their general cultural experience. We are never going to be able to teach everything and much will come up as we teach, but there are some things that we can include in our schemes of work. We can do the following:

We decided to work backwards in my previous department. We thought about the essential cultural knowledge that was missing when they arrived at GCSE and tried to embed it at KS3. Alongside this we considered what was missing generally and tried to include as much as we could that would be useful in life. Biblical allusions and Greeks, Romans and Rhetoric were placed into year 7, for example. It is something that is very hard to get right, and we are never going to give students all the cultural capital that they are lacking compared to their more privileged counterparts, but we can give them as much as we can to help them succeed.

Of course, alongside this we also have to have the added discussion around including and celebrating the cultures and backgrounds of all of our students, but it is perhaps easier to attempt to unpick these separately. Addressing cultural poverty is more thinking about the cultural knowledge which students might come across at various points, and which give them the confidence to tackle new texts for themselves.

Vocabulary

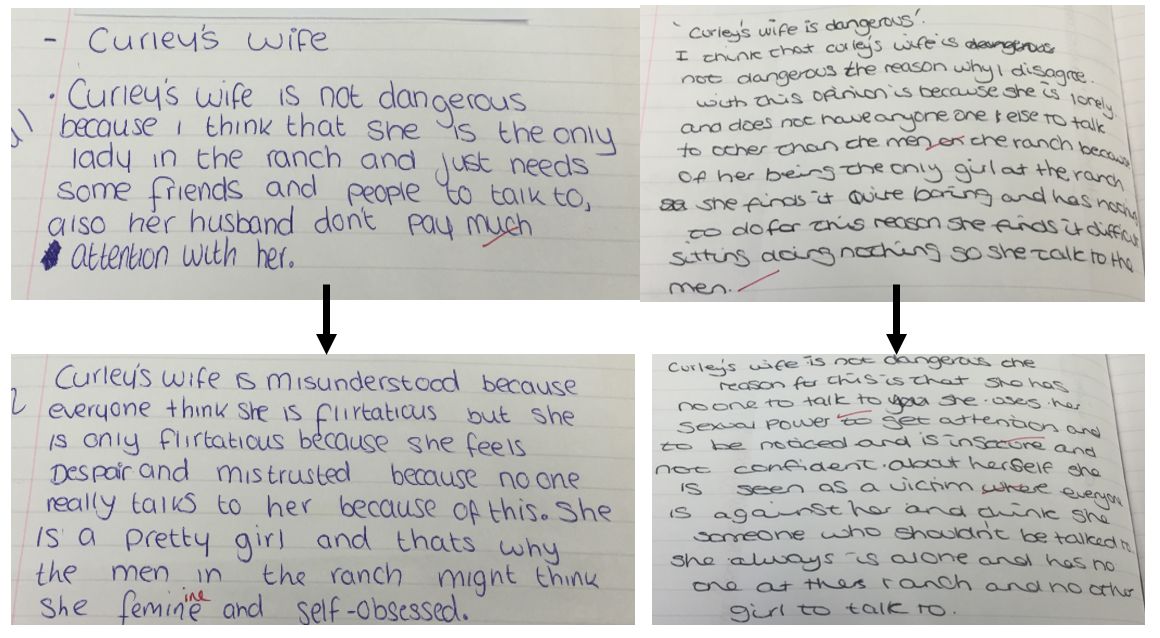

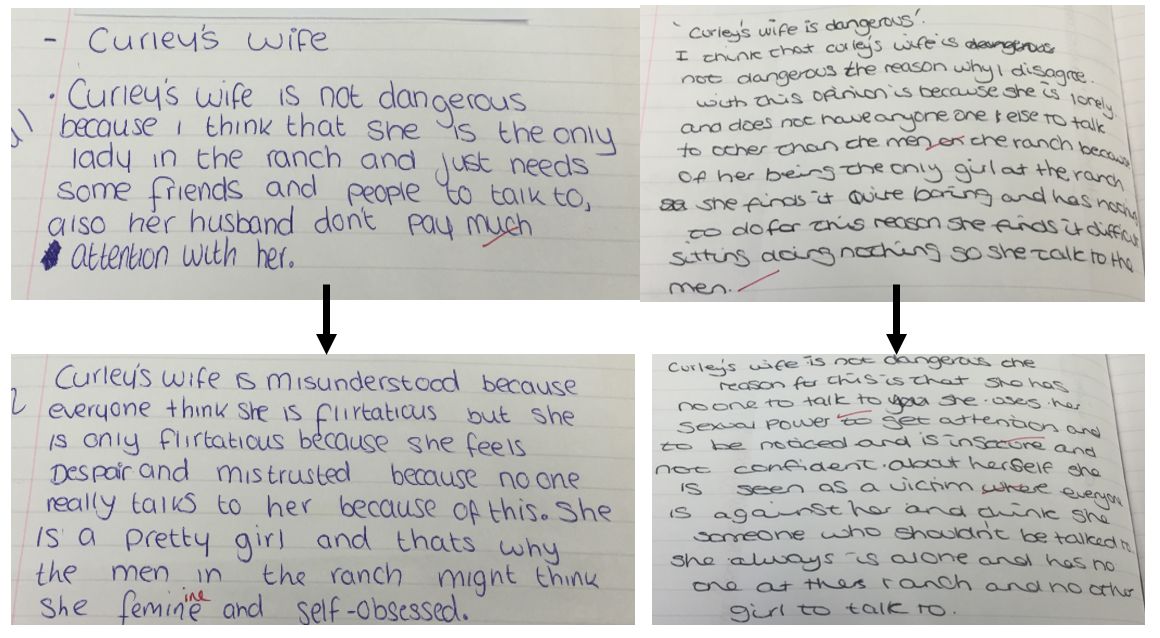

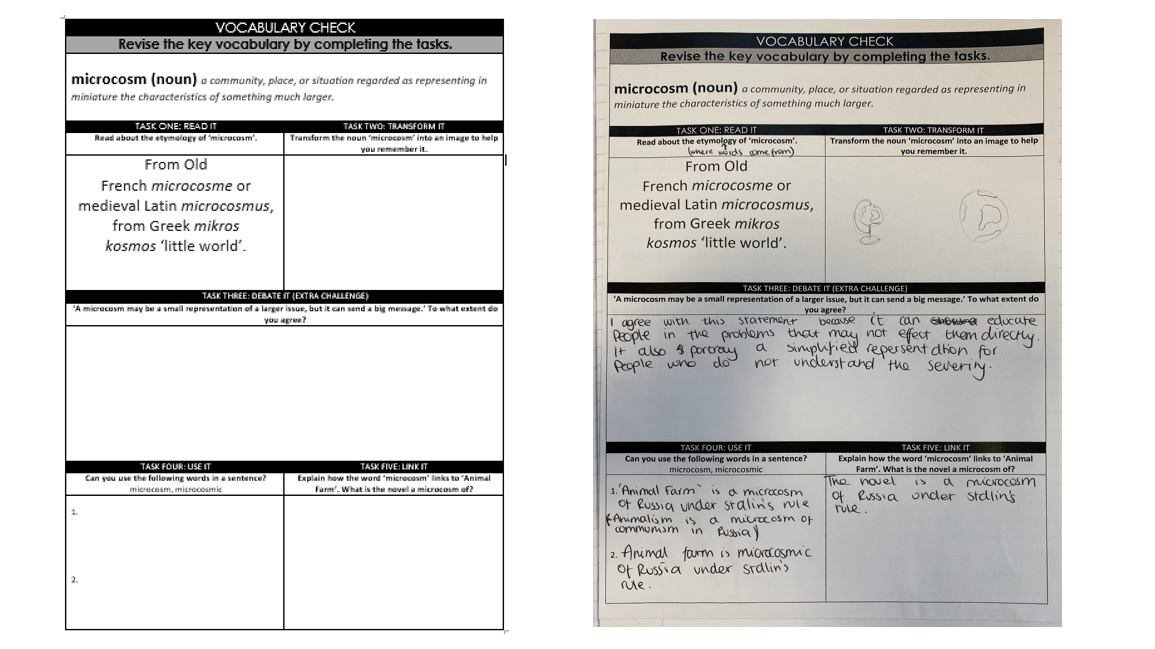

We all know the importance of vocabulary. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to have a limited vocabulary and be lacking in ‘word wealth’. There has been a huge push over the last few years to think about how we teach vocabulary within our lessons. Having a bank of words at our disposal is essential for us to be able to express ourselves effectively and succinctly. I blogged previously about a trial I did a few years ago where I focused on vocabulary, but very simply, it proved to me that it was one of the simplest and quickest things that we could do to improve a student’s writing. It is also important when teaching pupils with EAL to give them the tools to express themselves. Too often EAL students are put in lower sets because they don’t have the vocabulary yet to be able to express themselves, and in some ways when it comes to vocabulary, we should understand that some of our disadvantaged pupils equally need to be taught the vocabulary that will help them to succeed.

Lots of people have written about vocabulary and I will link further reading at the end of this blog, but essentially, teach them it and they will use it. Hopefully you can see below the impact that it may have on writing.

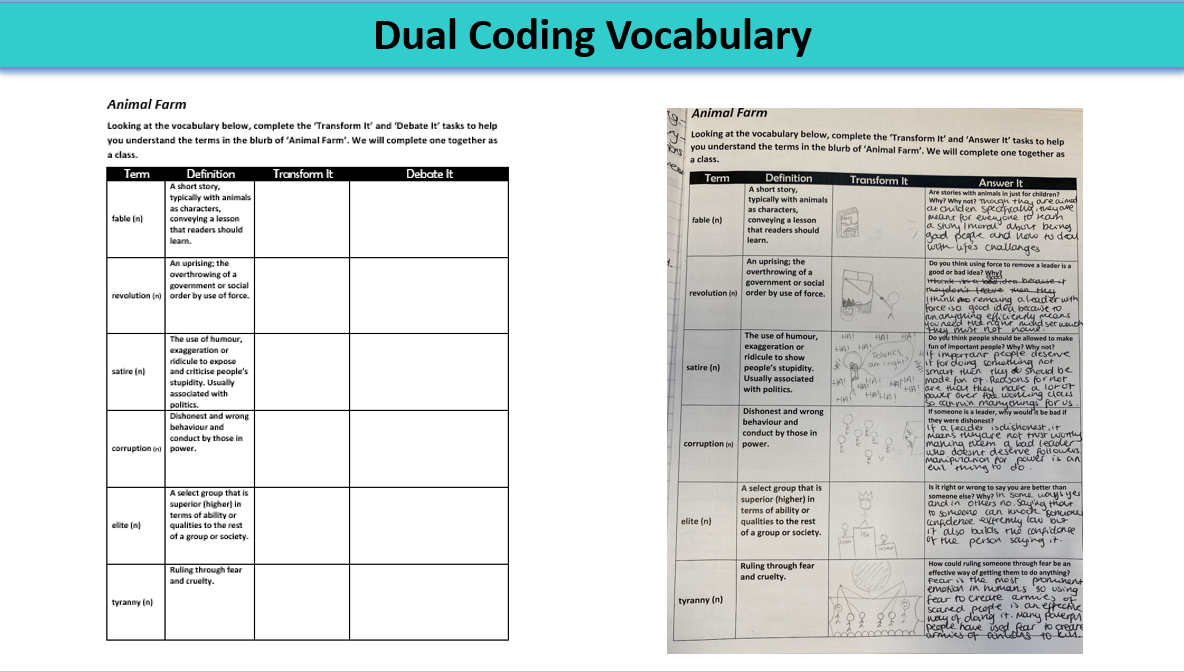

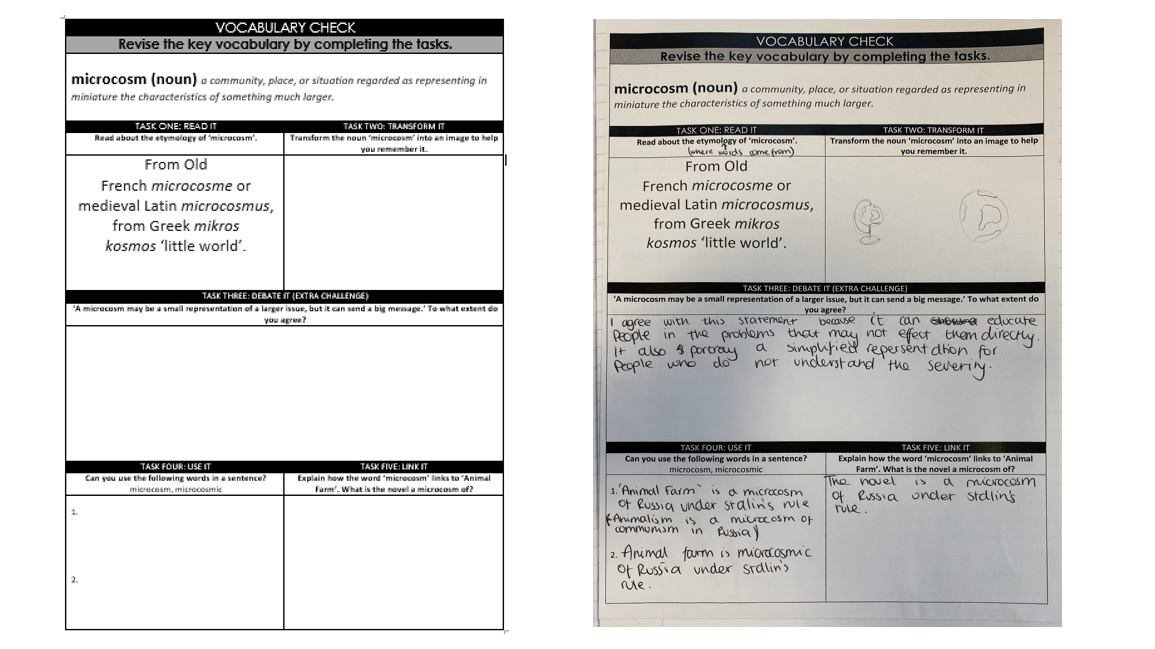

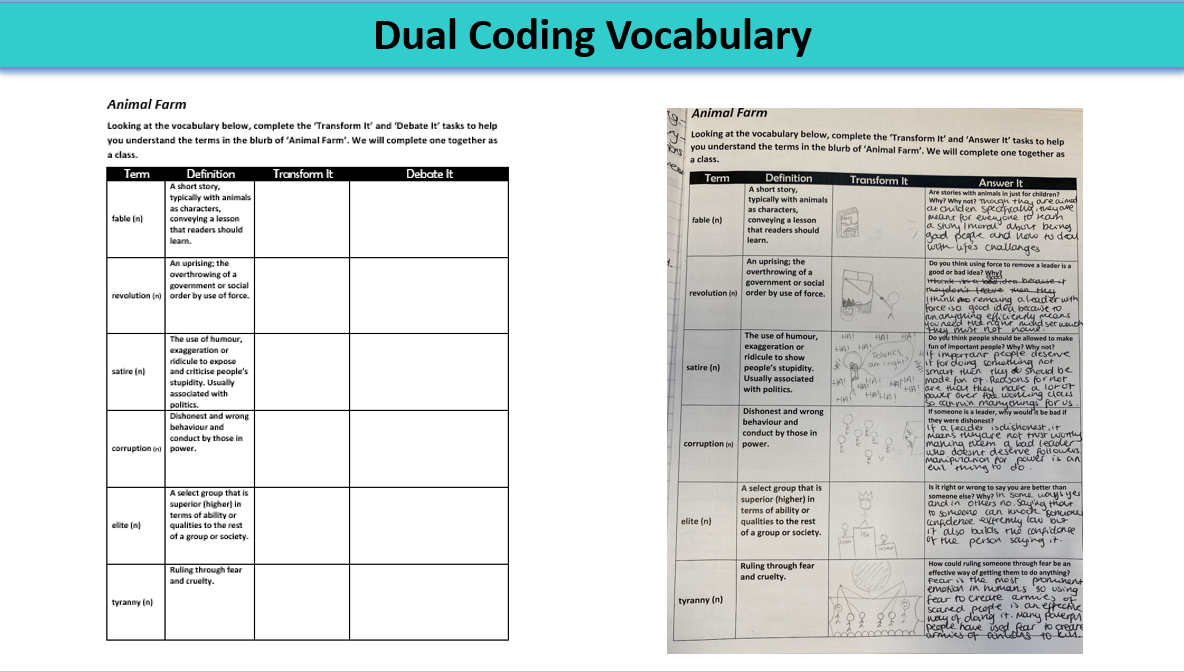

Dual coding also works wonders. Students can really play with he meaning of words and think about what might help them to remember meanings. The resources below are from the brilliant Stuart Pryke.

Reading

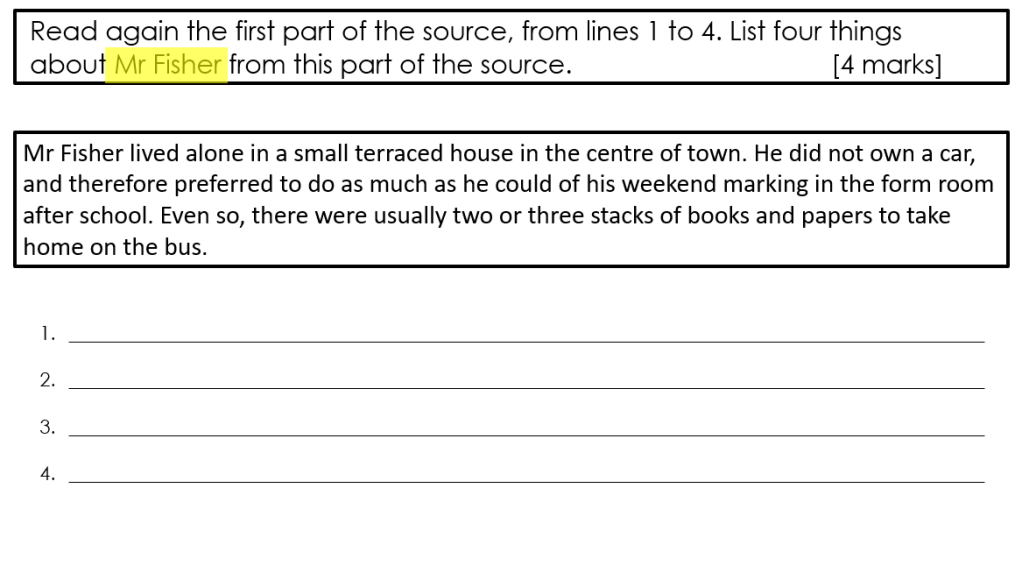

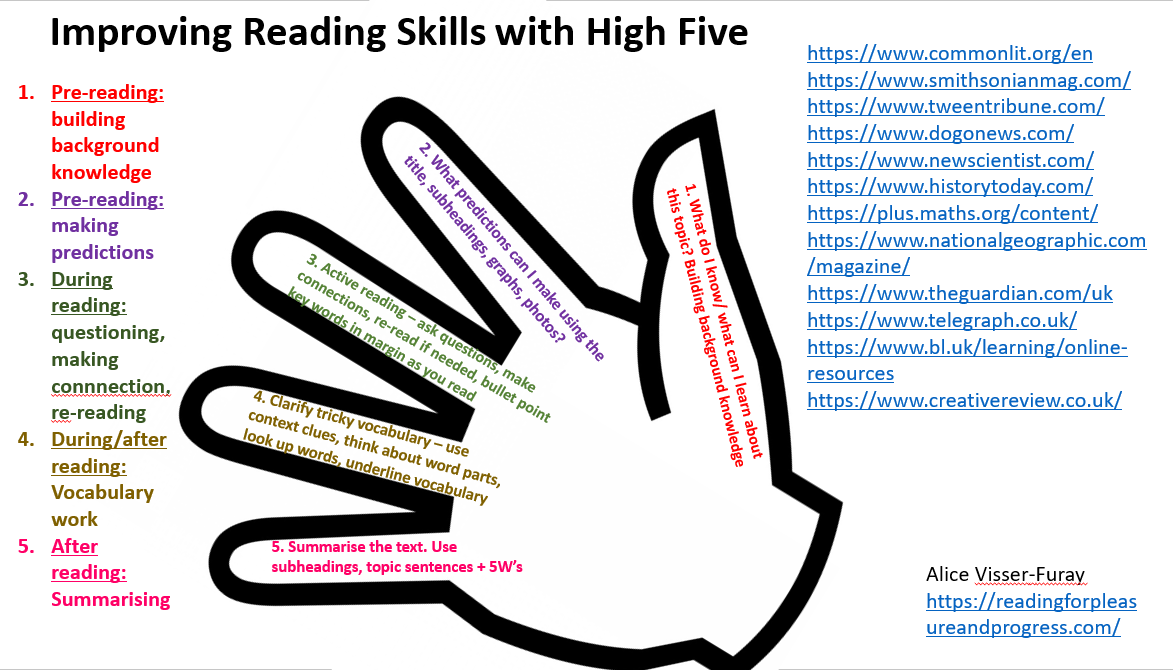

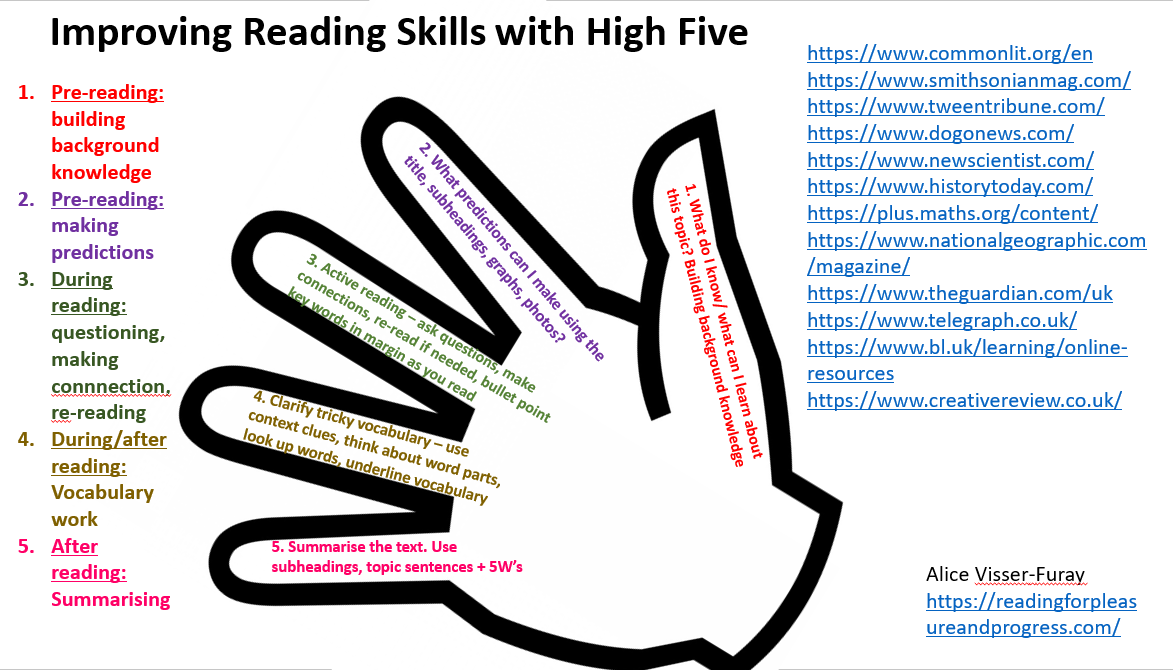

In my experience, disadvantaged students are often lacking in confidence when faced with a new text. I had the privilege of listening to Alice Vissar-Furay talk at a conference about the strategies that she had been working on within her school. I encourage you to read her blog, which is also full of resources and ideas, and an explanation of how they teach students to read and unpick new texts.

I was sat at the conference with Stuart Pryke, who then went back and produced a brilliant lesson (A Christmas Carol – lesson 13) using the strategies for A Christmas Carol. It really does work well; students read something very difficult but felt extremely clever by the end of it. They used the same strategies again with other texts and articles, and it certainly helped them to feel confident when faced with new texts.

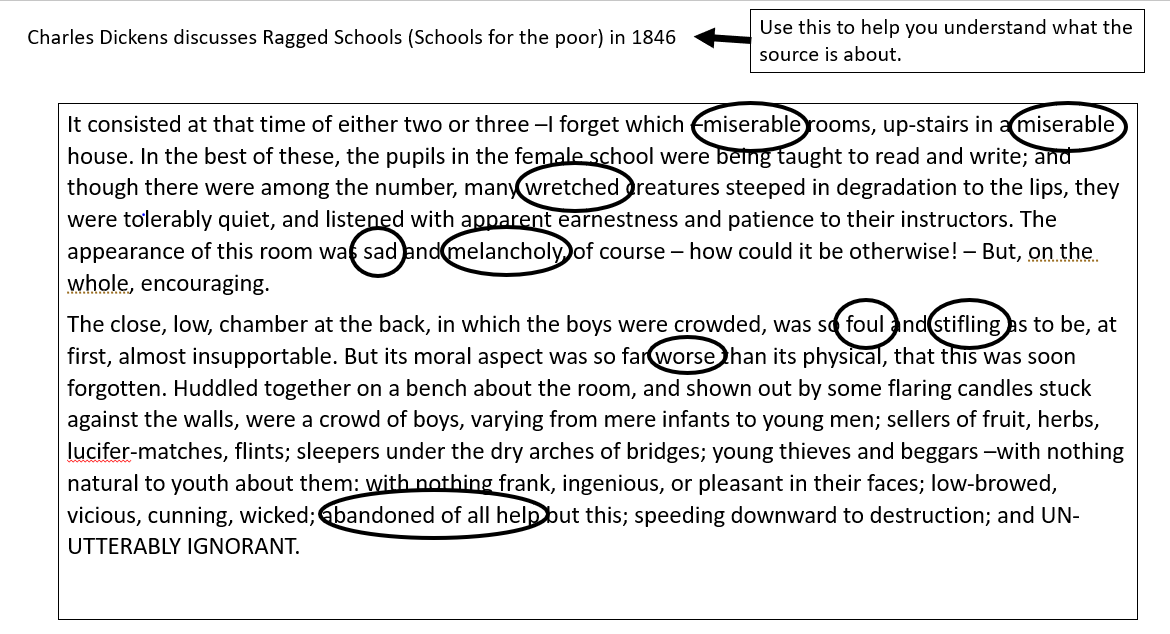

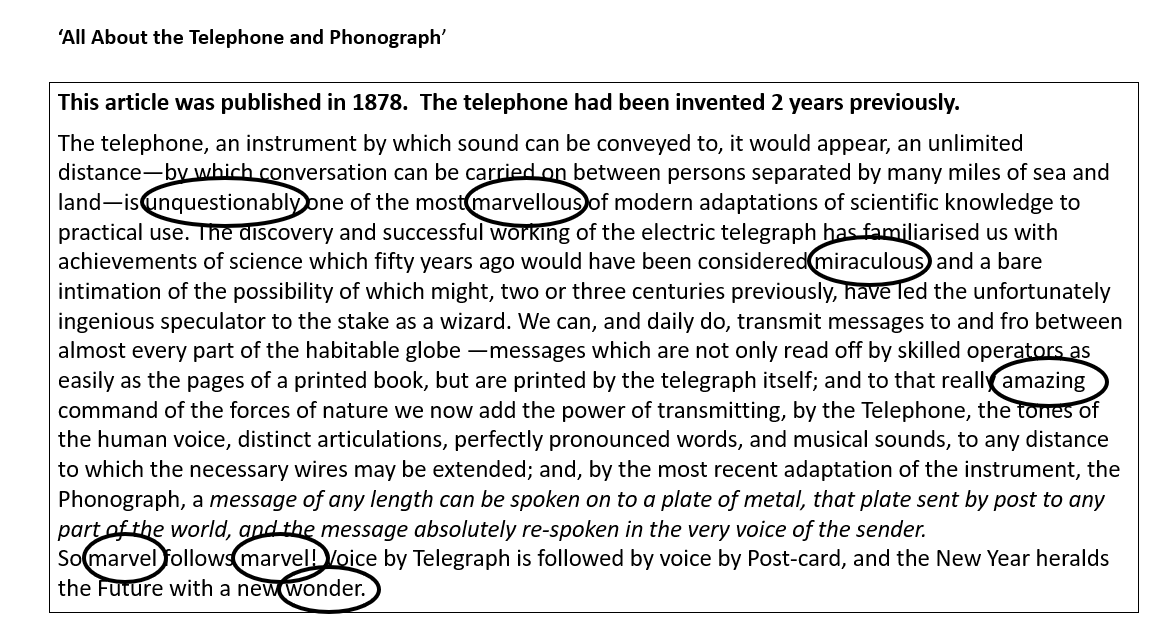

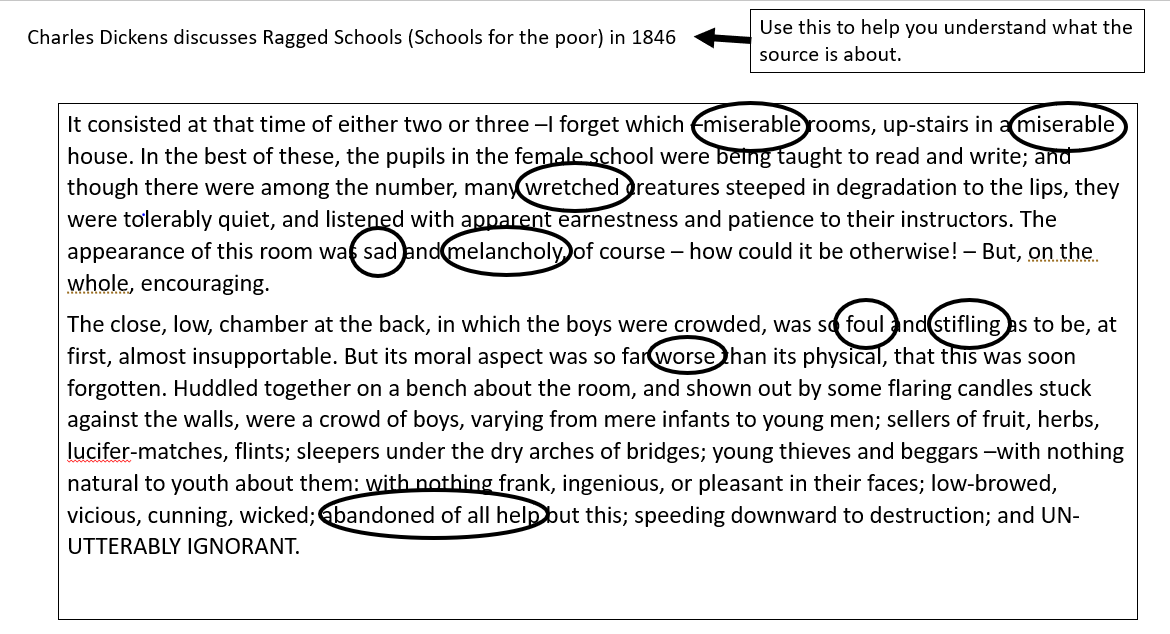

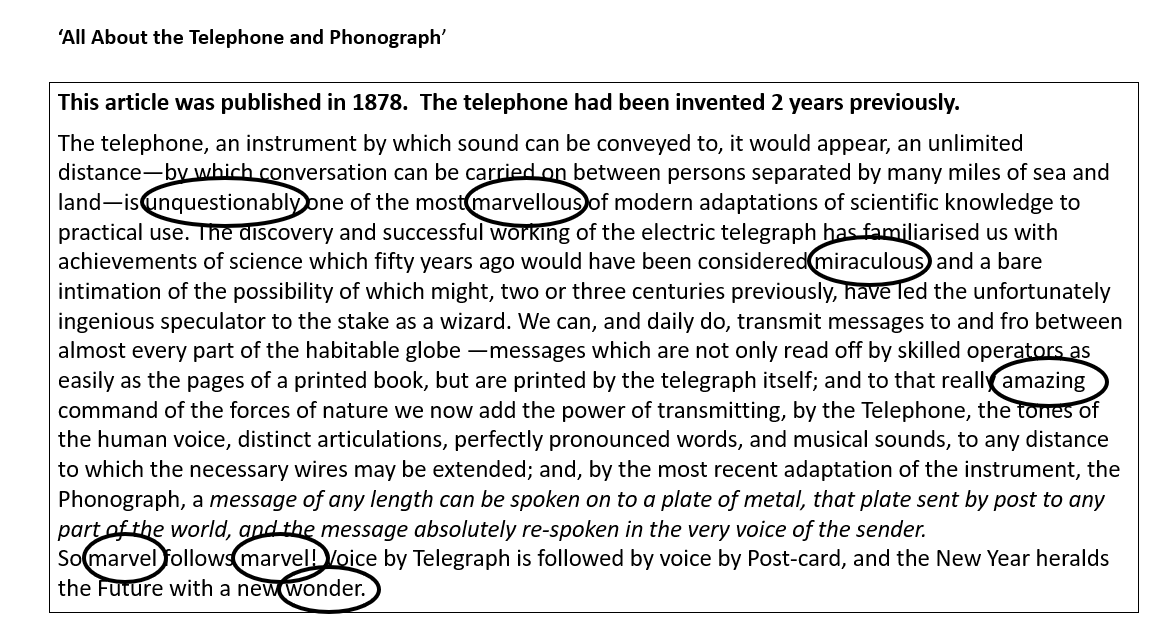

Another strategy that builds confidence is to show students how to read round words that they find difficult. More often than not, if a student feels like they don’t understand a text, they won’t write about it – often, it is the unseen 19th century non-fiction text that can make students feel as if they are a failure. Giving students a difficult text and asking them to pick out what they can understand and help to build confidence. The two texts below I gave to my year 11 class and asked them to highlight the words that they did know. In both cases they could tell me what they thought the reader’s opinion was, even if they couldn’t understand the whole text and go on to write a response. As a task, it helped them to realise that there is always something there to write about, and always something that they will understand.

I had the pleasure of teaching 900 students at GCSE In Action last year and when I talked about this there was lots of nodding enthusiastically, so it is clearly something that worries lots of students.

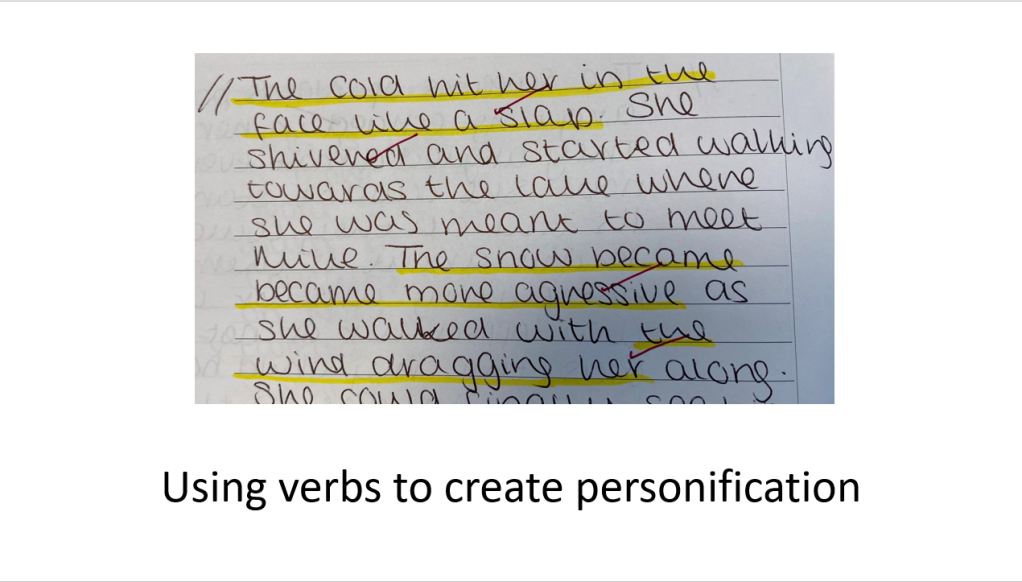

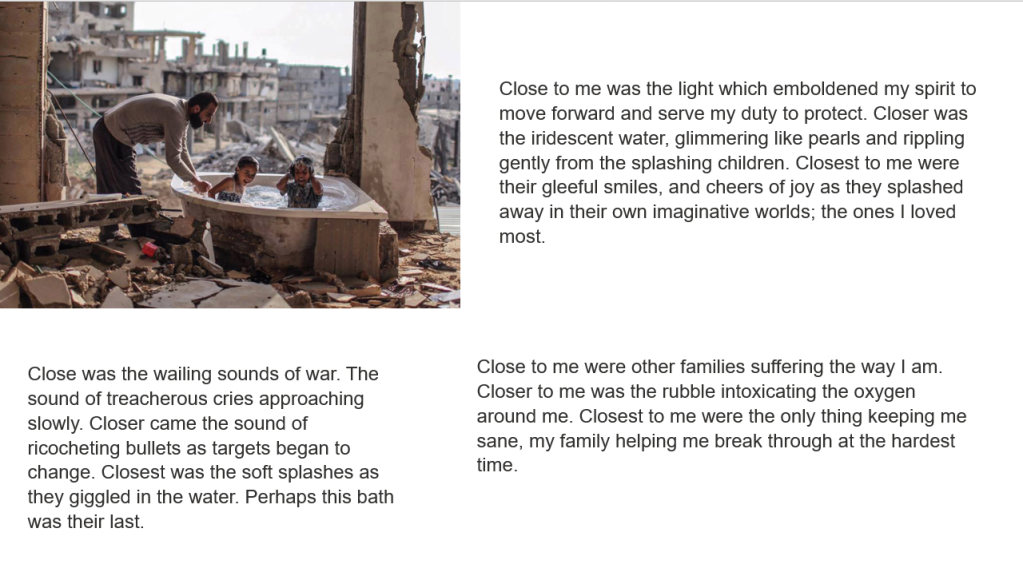

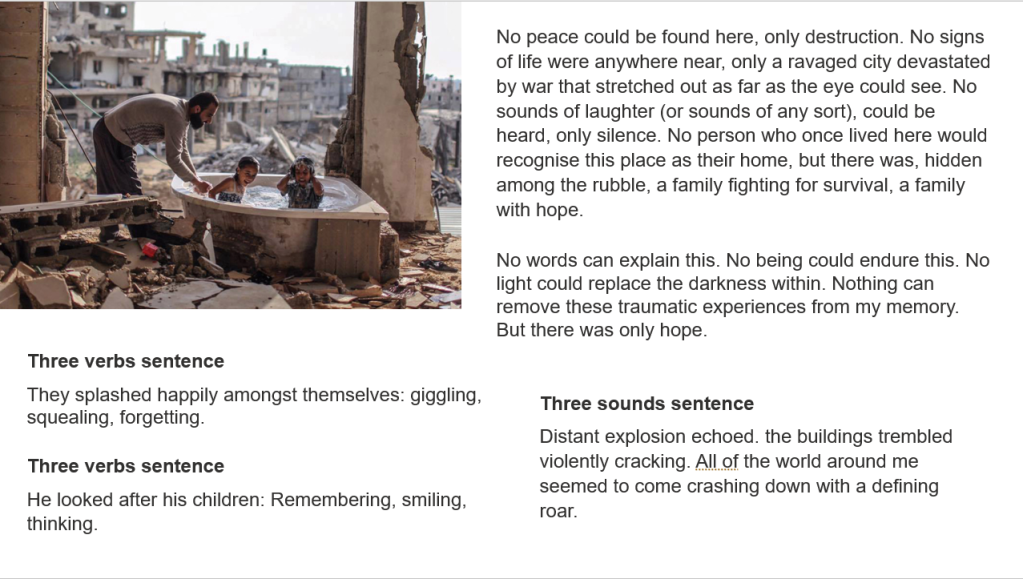

Building Writing Skills

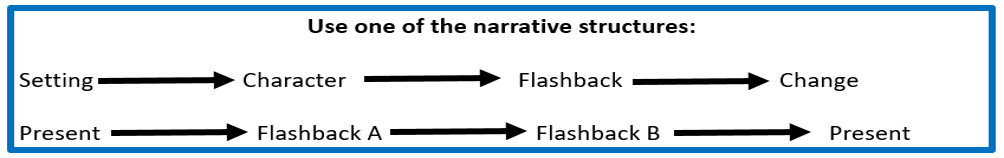

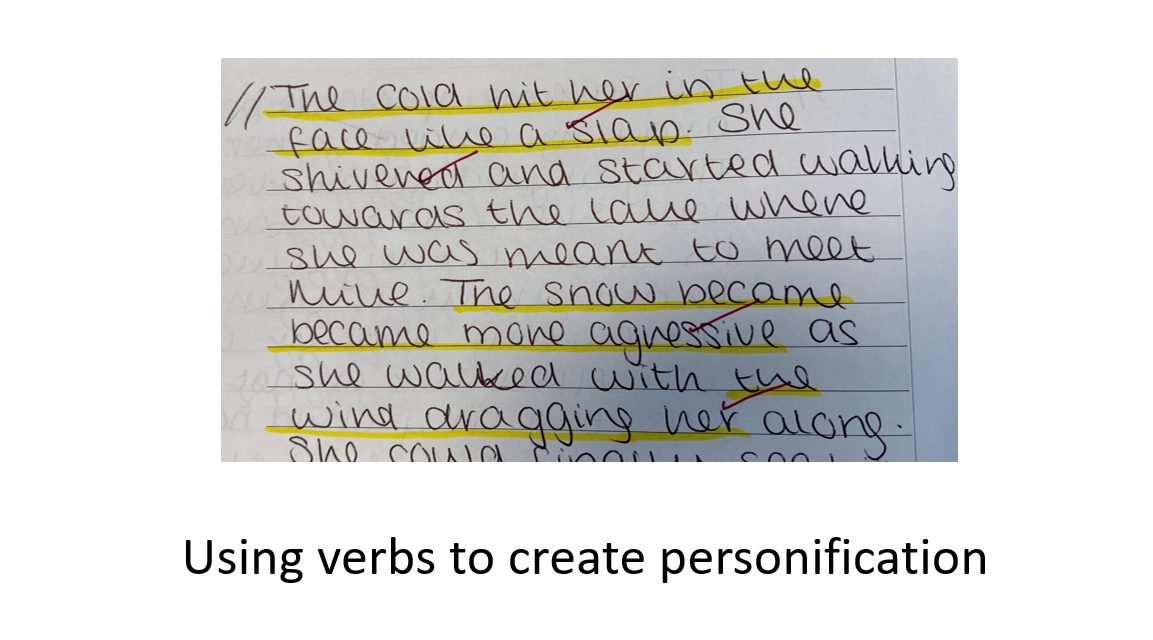

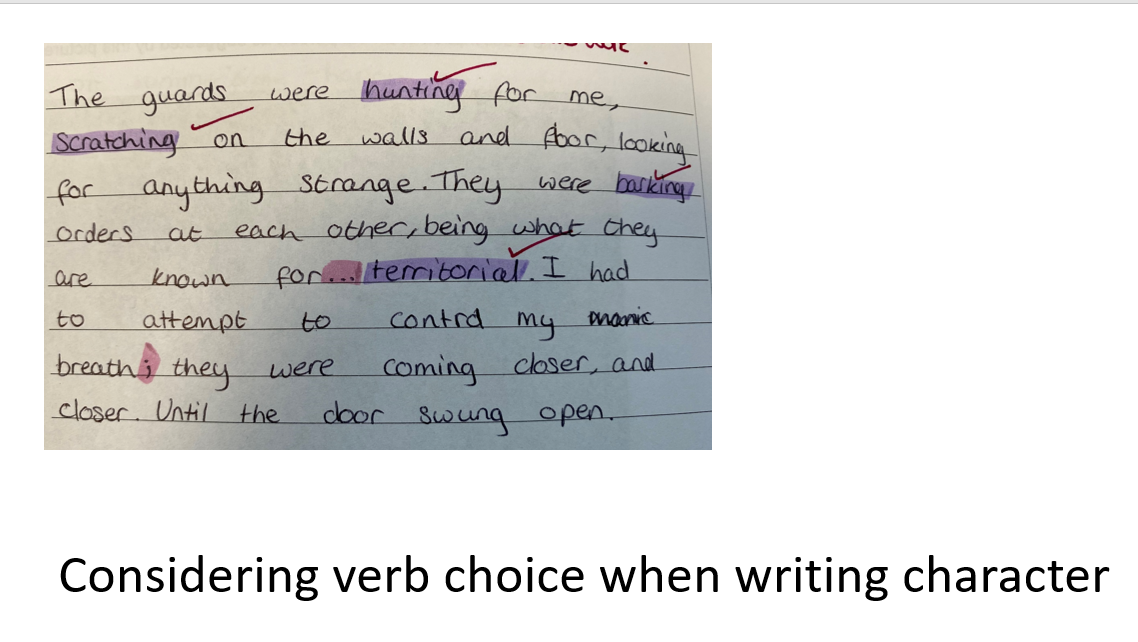

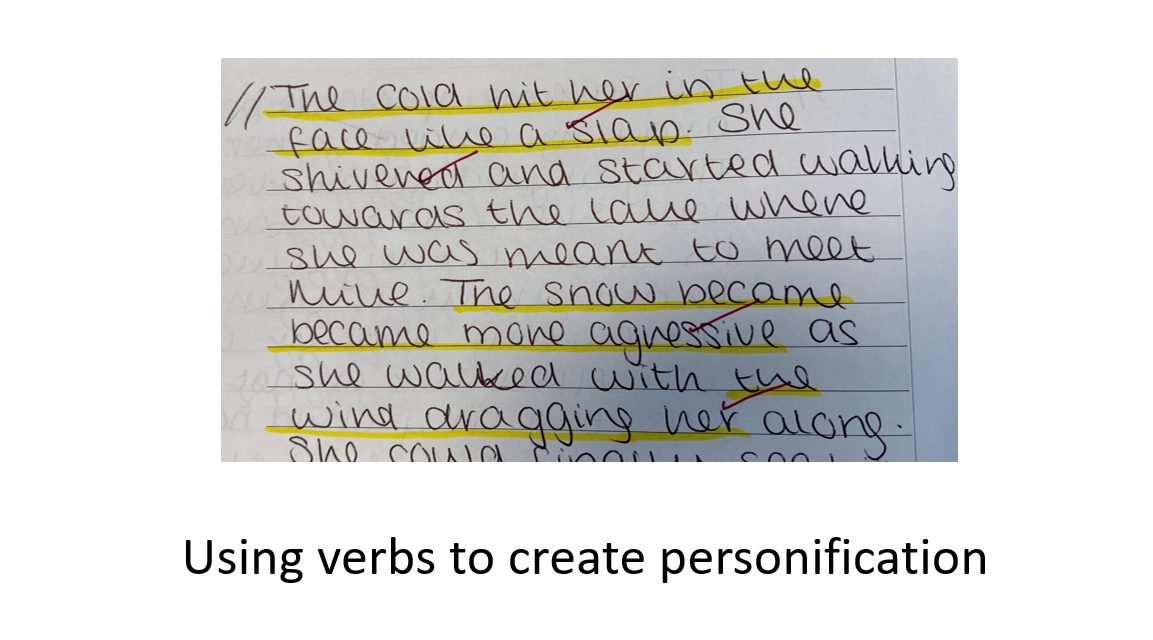

We often expect students to write narratives and creative responses without making sure that they have played with all the small skills that make an interesting and skilful piece of writing. On top of that, they will need to do it in just 45 minutes in an exam. Examiners complain of overly long, rambling, unstructured responses, planned on a narrative arc of novel length, that they will never be able to write in a month, let alone the 45 minutes given. Spending time teaching interesting ways of writing and focusing on the small skills that make good writing encourages confidence in students expressing their own ideas, something that they are often afraid to do.

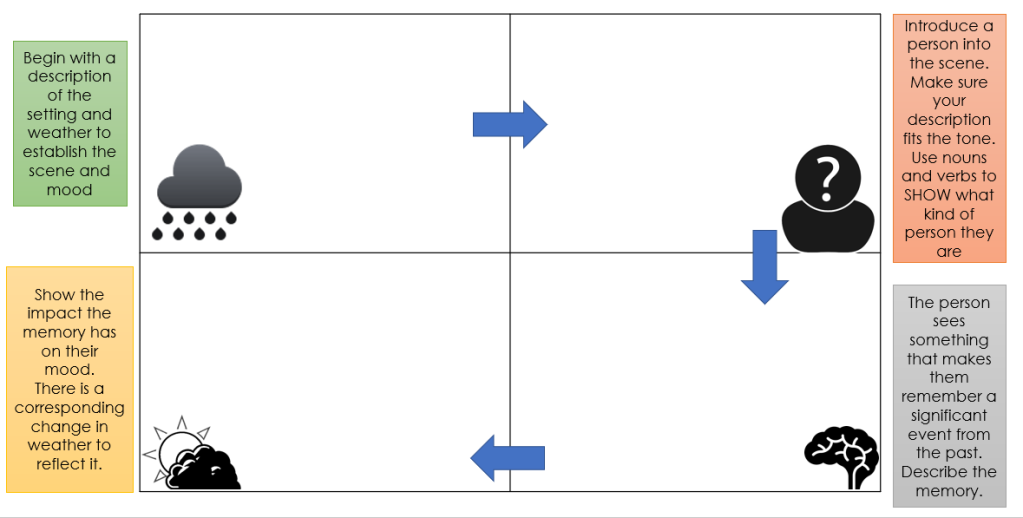

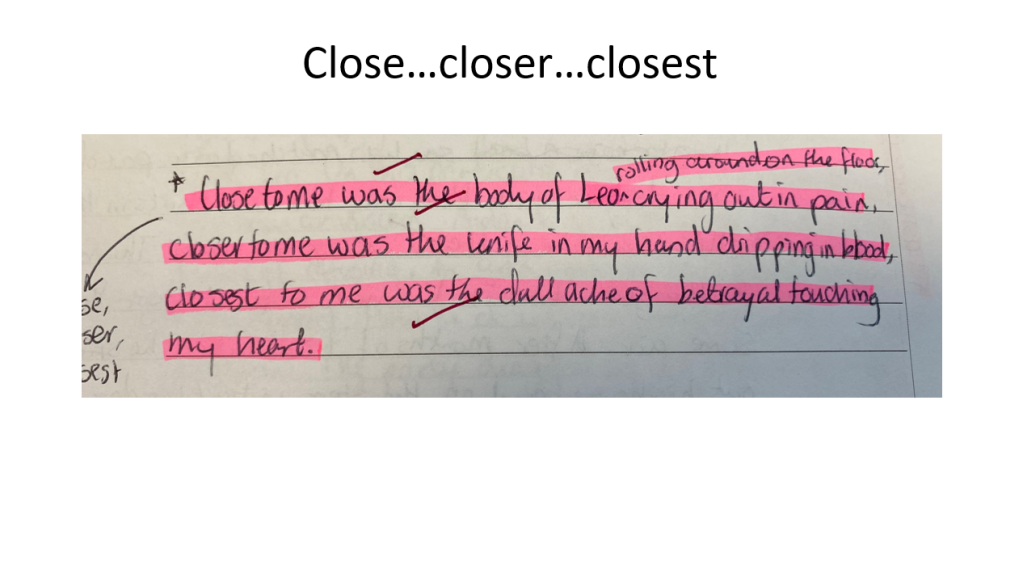

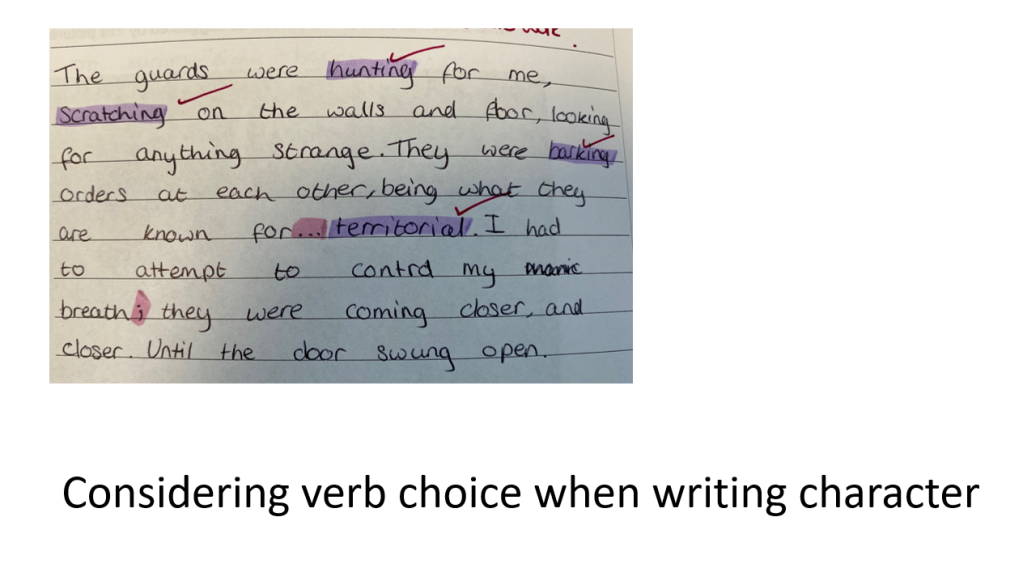

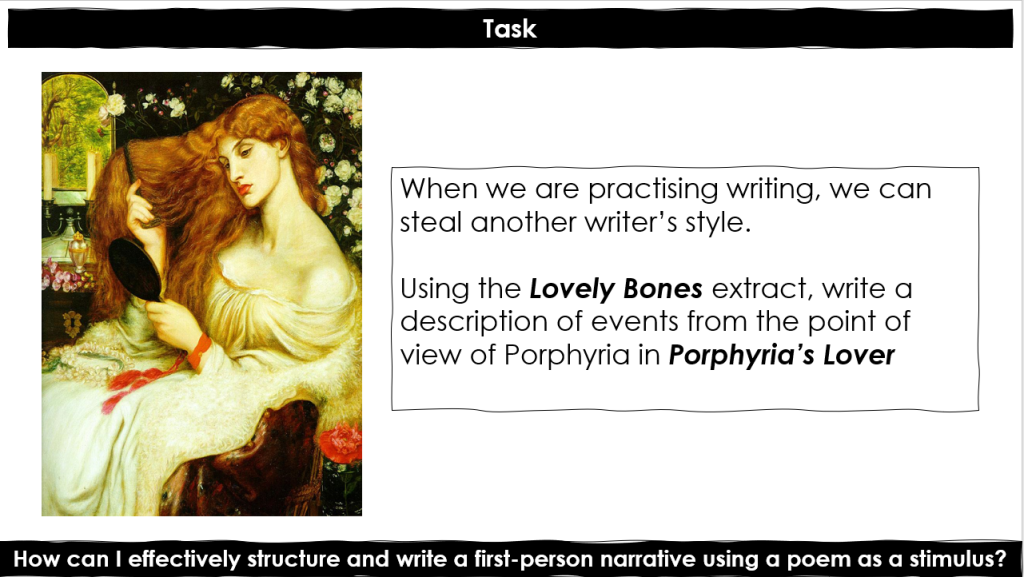

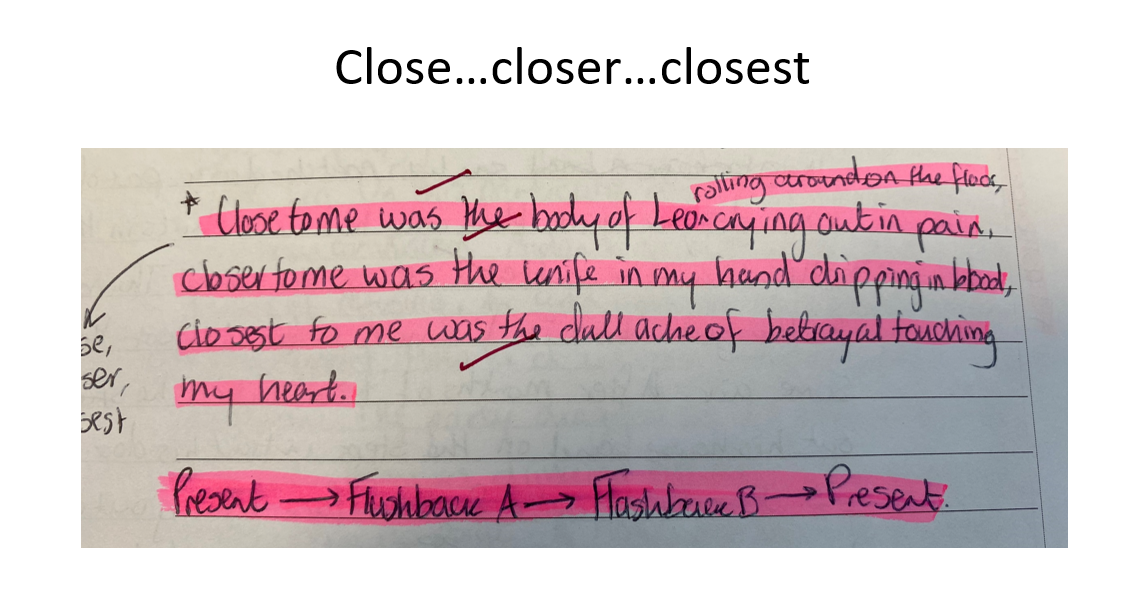

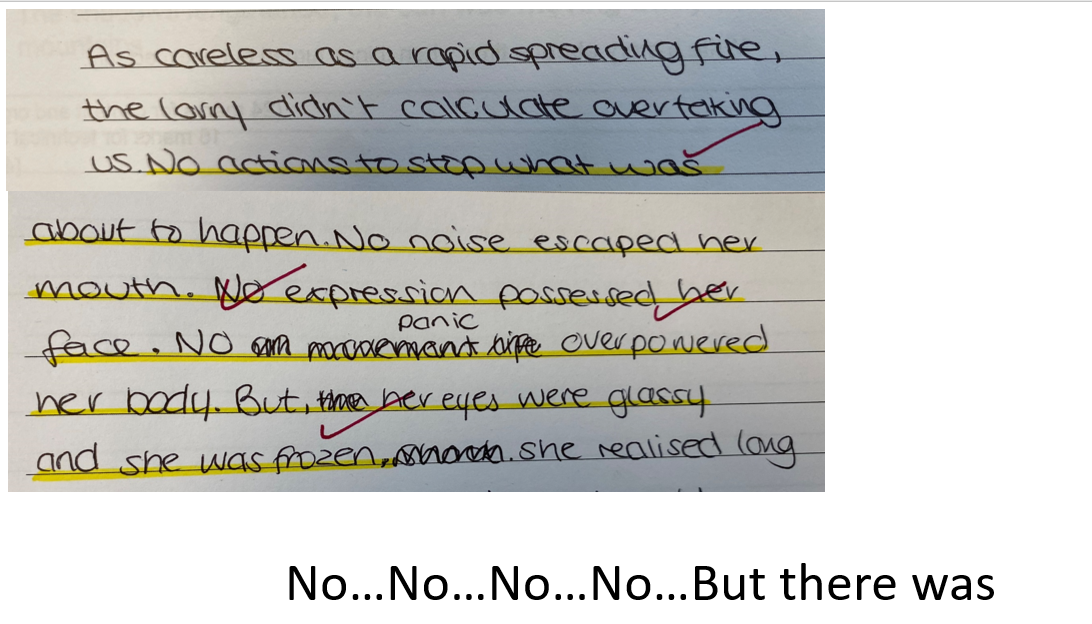

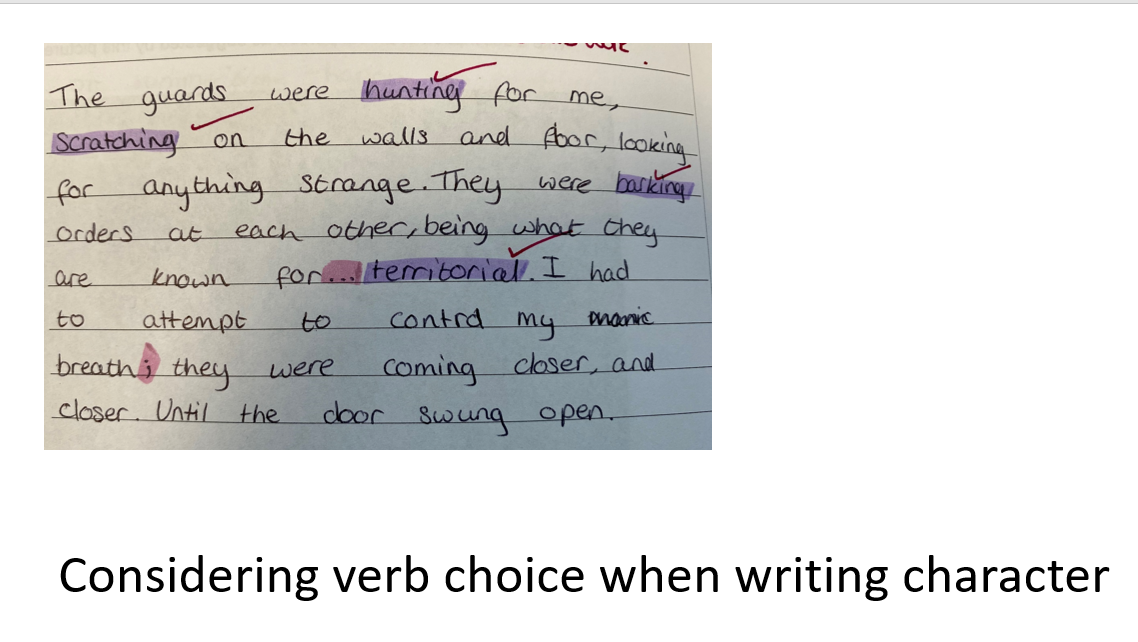

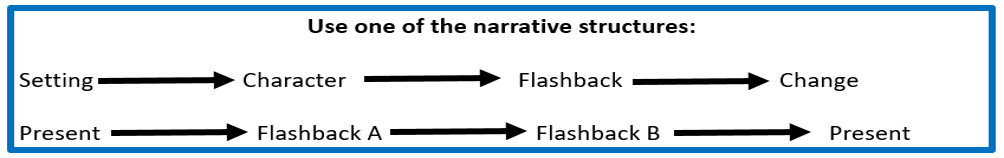

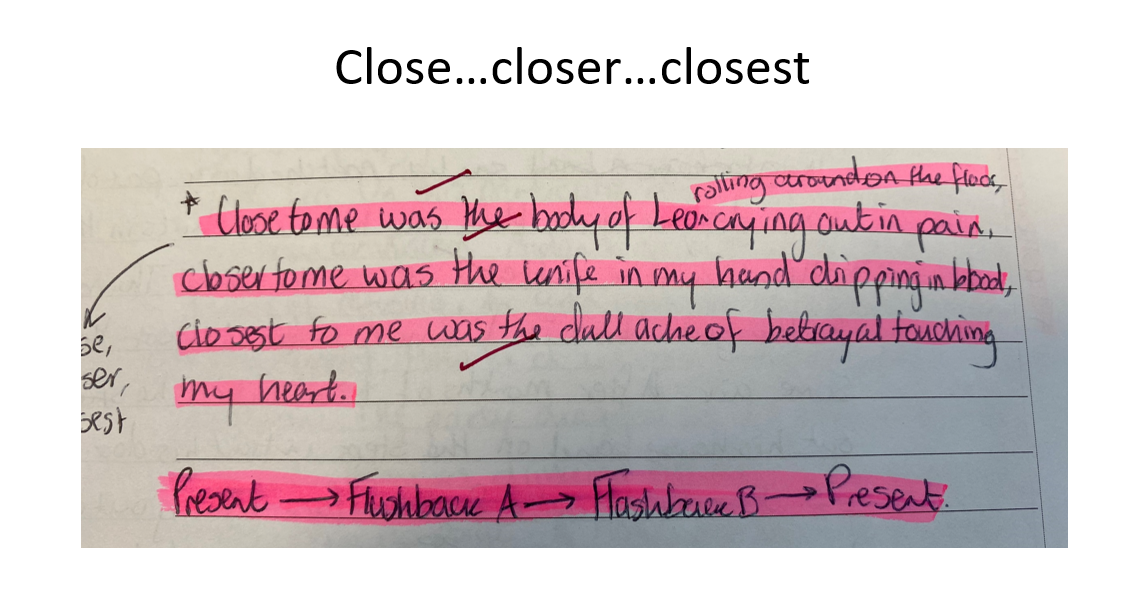

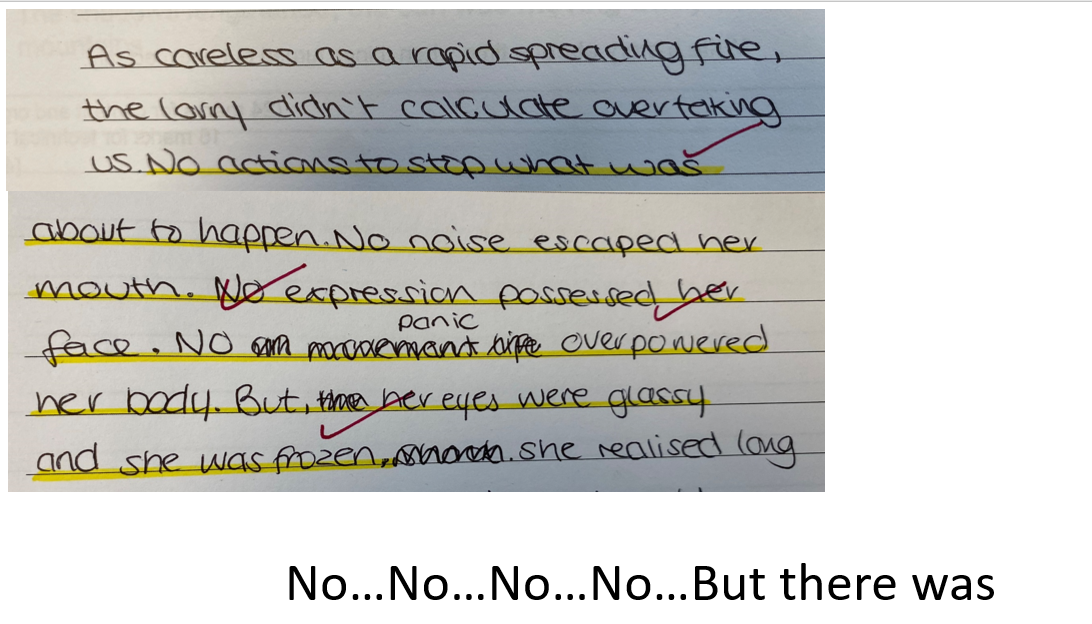

We spent time as a department last year teaching year 10 two structures that we wanted students to practise using. The first was a structure written about by @EDmerger and adapted into a lesson by @SPryke2. I had used it with year 11 to great effect and had seen some wonderful writing produced using the structures. The second was a structure that my brilliant colleague @HilesSophie had used to great effect within her classroom. The two structures were as follows:

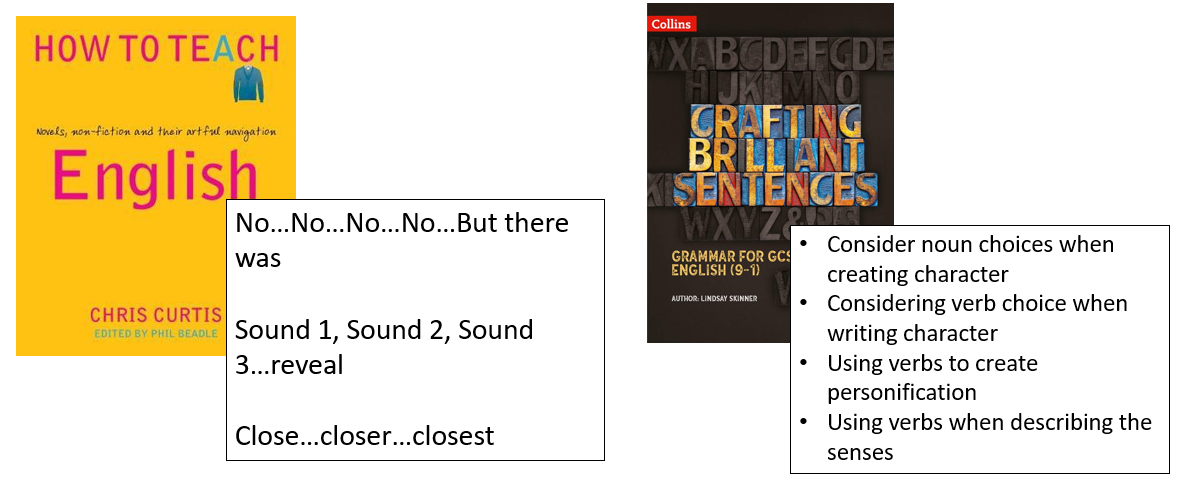

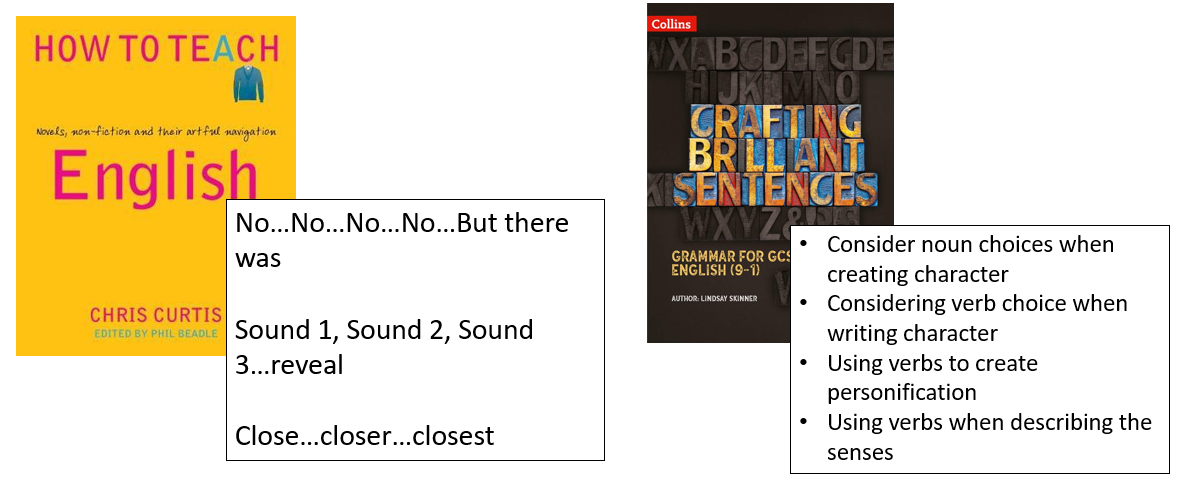

Alongside this we also wanted them to be considering the nuts and bolts of writing more closely. Chris Curtis’s (Xris32) How To Teach English and Lindsay Skinner’s Crafting Brilliant Sentences are both excellent for strategies and resources to support writing. We picked a handful of ideas from each, 3 paragraph structures from Chris’s book and a focus on noun and verb choices from Lindsay’s book. These were introduced along with the text structures and students spent lessons practising and playing with each.

Students then sat a mock paper and were told to use the structures and strategies that they felt comfortable with. When marking the mock papers we looked at where they had been used, how students structured their work and their marks on the writing task, compared to previous cohorts at that time of year.

What was most interesting was that even though there were students that slipped back into random story-telling (you know, the ones who just re-tell the plot of Fast and Furious), the majority not only answered the question, but answered it well, using the strategies that they had been taught. Knowing how to effectively structure work had given them the confidence to do it, but also their creativity wasn’t stifled; narratives were varied and interesting but crafted far more successfully than we had seen previously. It also stopped the pages and pages of response. Students wrote 2-3 sides of well-crafted and considered response and average marks were considerably higher than we had seen in previous years at the same time.

Some might argue that teaching set structures stifles creativity, but when you are teaching students whose level of disadvantage means that they may not read a wide range of fiction or struggle to have ideas, it gives them a lever to start from. It gives them a toolkit to take from, and I would argue that toolkit actually encouraged creativity.

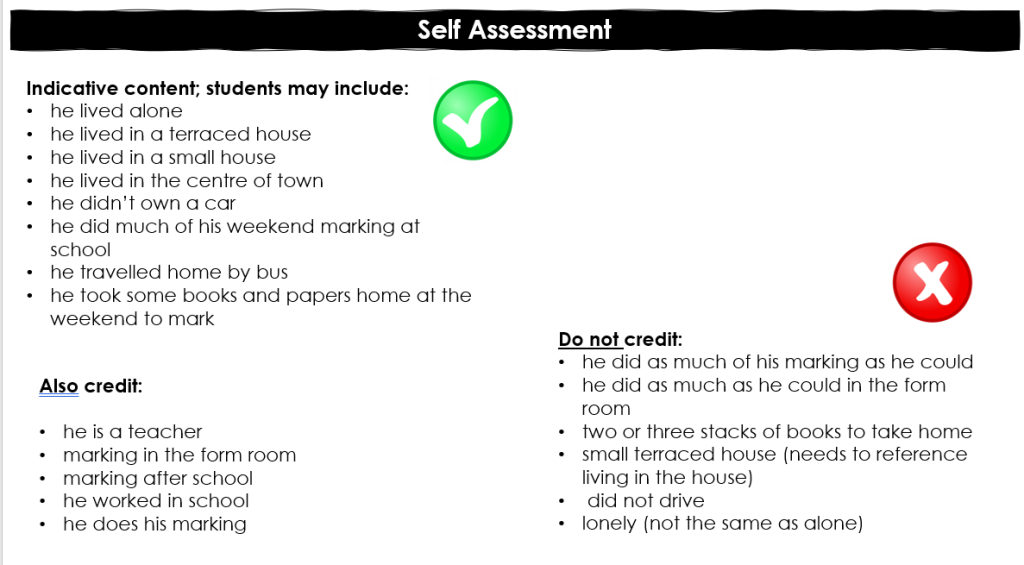

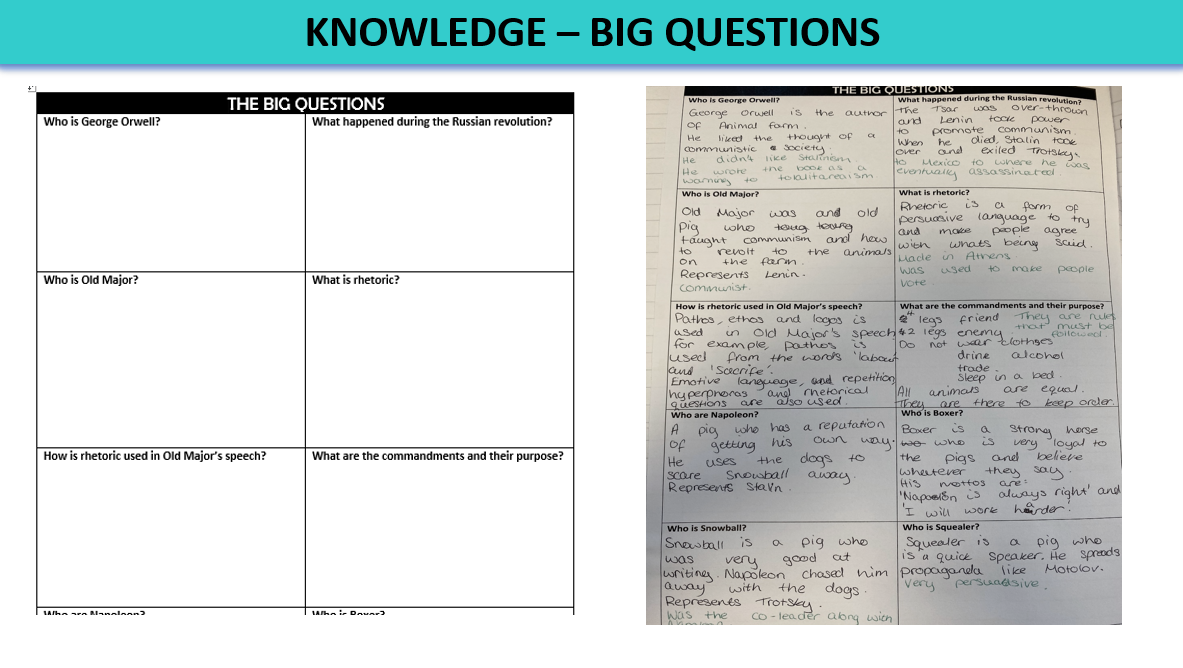

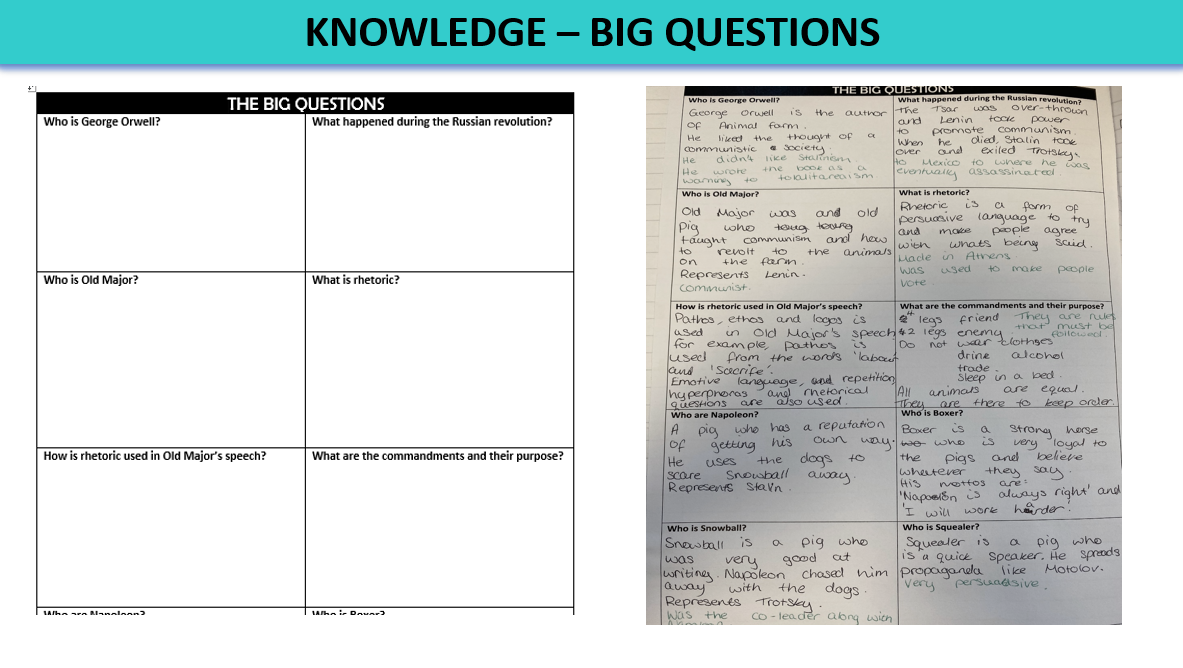

Knowledge retention

One of the biggest issues that we found, particularly with the literature texts, is that students didn’t know enough to write about the texts. They didn’t have the knowledge to be able to talk about characters, themes, or to generally have an opinion about a text. We’d seen lots written about the use of Big Questions and decided to consider how we could use them to make sure that students had the vital basic knowledge that they needed to succeed. It also meant we could be sure that there was a level of consistency across the department; we knew that all students would be taught the essential knowledge that we wanted them to have, but there was a level of autonomy in how that was taught by individual teachers. Again, I am grateful to Stuart Pryke who consolidated my thinking and showed me his way of doing.

We started at KS4, adapting all schemes of work to cover the essential knowledge that we wanted all students to have. As a caveat, we didn’t forget about skills – skills were interleaved within the lessons. KS4 students had a copy of all the Big Questions in their books and would answer the question after the lesson. After approximately every 8-10 lessons, they would receive a blank copy of the Big Questions and be tested on what they remembered. Once they had filled in the sheets, they went round and spoke to others, adding anything extra in green pen. This very quickly allowed a teacher to check students learning, and see any aspect that perhaps needed re-visiting at either a class or individual level. It was noticeable than when this was done well, students performed better in both extended writing and mock papers as there was significant increased confidence in what they knew about a text.

To test the effect further, we trained a group of year 7s who visited year 11 lessons once every few weeks with a list of the Big Questions, and asked random students to answer the questions they chose. They recorded their answers and we could see what knowledge was being retained. Year 7 enjoyed the responsibility, but there was also a level of confidence and pride in year 11 that they could answer questions and show off their learning.

This was then rolled out to cover aspects of language teaching and to our KS3 schemes of work. Below is an snapshot of our planning for a year 7 scheme of work – Greeks, Romans and Rhetoric.

How does this help tackle disadvantage? Well it is one way of ensuring that all students have the same level of challenge and there is a level of consistency. It gives students a confidence that they do know something about a text and in my personal experience, it pushed those who struggled with English to have confidence to express an opinion, because they knew something about a text.

Tackling the ‘disadvantage gap’ is something that we know is going to be in the news over the coming months. I know there are teachers across the country frustrated at how much learning time has been lost, worrying about the effect that it has had on our young people. We know that all students have lost out, but we have to be realistic and understand that there are those who have struggled more than others. Those without a laptop or device, with no wifi, or limited data. I have seen people saying, ‘but all students have a phone’ – that really shows a lack of understanding about all the factors that make a student disadvantaged in comparison to some of their peers.

I have moved schools, and moved across the country – up and west. I choose where I wanted to work based on the fact that I find working with some of our most disadvantaged young people the most rewarding and important. I know I have a lot to learn, disadvantage does not look the same everywhere, and I have yet to meet the students I will be spending my days with. But I am excited and looking forward to working with what I have already seen are some of the most passionate and forward-thinking colleagues, who clearly know and love our cohort – and I will too.

And across the country, we will do what we can…because we always do.

Further Reading

Closing the Vocabulary Gap – Alex Quigley

https://www.theconfidentteacher.com/

How to Teach English Literature – Jennifer Webb

https://funkypedagogy.com/

How To Teach: English – Chris Curtis

http://learningfrommymistakesenglish.blogspot.com/

Making Every English Lesson Count – Andy Tharby

https://reflectingenglish.wordpress.com/

Bringing Words to Life – Isabel Beck et al

Reading Reconsidered – Doug Lemov et al

Alice Visser-Furay

https://readingforpleasureandprogress.com/

The Writing Revolution – Judith C Hochman et al

Dual Coding with teachers – Oliver Caviglioli